Across The Plains

It was as much as I could carry with convenience even for short distances, but it insured me plenty of clothing, and the valise was at that moment, and often after, useful for a stool. I am sure I sat for an hour in the baggage room, and wretched enough it was; yet, when at last the word was passed to me and I picked up my bundles and got underway, it was only to exchange discomfort for downright misery and danger.

I followed the porters into a long shed reaching downhill from West Street to the river. It was dark, the wind blew clean through it from end to end; and here I found a great block of passengers and baggage, hundreds of one and tons of the other. I feel I shall have difficulty to make myself believed; and certainly the scene must have been exceptional, for it was too dangerous for daily repetition. It was a tight jam; there was no fair way through the mingled mass of brute and living obstruction. Into the upper skirts of the crowd porters, infuriated by hurry and overwork, clove their way with shouts. I may say that we stood like sheep and that the porters charged among us like so many maddened sheep-dogs, and I believe these men were no longer answerable for their acts. It mattered not what they were carrying, they drove straight into the press, and when they could get no farther, blindly discharged their barrowful. With my hand, for instance, I saved the life of a child as it sat upon its mother’s knee, she sitting on a box; and since I heard of no accident, I must suppose that there were many similar interpositions in the course of the evening. It will give some idea of the state of mind to which we were reduced if I tell you that neither the porter nor the mother of the child paid the least attention to my act. It was not till some time after that I understood what I had done myself, for to ward off heavy boxes seemed at the moment a natural incident of human life. Cold, wet, clamour, dead opposition to progress, such as one encounters in an evil dream, had utterly daunted the spirits. We had accepted this purgatory as a child and accepted the conditions of the world. For my part, I shivered a little, and my back ached wearily; but I believe I had neither hope nor a fear, and all the activities of my nature had become tributary to one massive sensation of discomfort.

At length, and after how long an interval I hesitate to guess, the crowd began to move, heavily straining through itself. About the same time some lamps were lighted, and threw a sudden flare over the shed.

Read or download Book

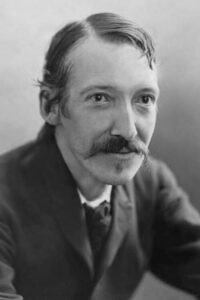

Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as Treasure Island, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Kidnapped, and A Child’s Garden of Verses.

Born and educated in Edinburgh, Stevenson suffered from serious bronchial trouble for much of his life but continued to write prolifically and travel widely in defiance of his poor health. As a young man, he mixed in London literary circles, receiving encouragement from Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse, Leslie Stephen, and W. E. Henley, the last of whom may have provided the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island. In 1890, he settled in Samoa where alarmed at increasing European and American influence in the South Sea islands, his writing turned from romance and adventure fiction toward a darker realism. He died of a stroke in his island home in 1894 at age 44.

A celebrity in his lifetime, Stevenson’s critical reputation has fluctuated since his death, though today his works are held in general acclaim. In 2018, he was ranked just behind Charles Dickens as the 26th-most-translated author in the world.

Early writing and travels

Stevenson was soon active in London’s literary life, becoming acquainted with many of the writers of the time, including Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse, and Leslie Stephen, the editor of The Cornhill Magazine, who took an interest in Stevenson’s work. Stephen took Stevenson to visit a patient at the Edinburgh Infirmary named William Ernest Henley, an energetic and talkative poet with a wooden leg. Henley became a close friend and occasional literary collaborator, until a quarrel broke up the friendship in 1888, and he is often considered to be the inspiration for Long John Silver in Treasure Island.

Stevenson was sent to Menton on the French Riviera in November 1873 to recuperate after his health failed. He returned to better health in April 1874 and settled down to his studies, but he returned to France several times after that. He made long and frequent trips to the neighborhood of the Forest of Fontainebleau, staying at Barbizon, Grez-sur-Loing, and Nemours and becoming a member of the artists’ colonies there. He also traveled to Paris to visit galleries and theatres. He qualified for the Scottish bar in July 1875, aged 24, and his father added a brass plate to the Heriot Row house reading “R.L. Stevenson, Advocate”. His law studies did influence his books, but he never practiced law; all his energies were spent on travel and writing. One of his journeys was a canoe voyage in Belgium and France with Sir Walter Simpson, a friend from the Speculative Society, a frequent travel companion, and the author of The Art of Golf (1887). This trip was the basis of his first travel book An Inland Voyage (1878).

Reflections on the art of writing

Stevenson’s critical essays on literature contain “few sustained analyses of style or content”. In “A Penny Plain and Two-pence Coloured” (1884) he suggests that his approach owed much to the exaggerated and romantic world that, as a child, he had entered as proud owner of Skelt’s Juvenile Drama—a toy set of cardboard characters who were actors in melodramatic dramas. “A Gossip on Romance” (1882) and “A Gossip on a Novel of Dumas’s” (1887) imply that it is better to entertain than to instruct.

Stevenson very much saw himself in the mold of Sir Walter Scott, a storyteller with the ability to transport his readers away from themselves and their circumstances. He took issue with what he saw as the tendency in French realism to dwell on sordidness and ugliness. In “The Lantern-Bearer” (1888) he appears to take Emile Zola to task for failing to seek out nobility in his protagonists.

In “A Humble Remonstrance”, Stevenson answers Henry James’s claim in “The Art of Fiction” (1884) that the novel competes with life. Stevenson protests that no novel can ever hope to match life’s complexity; it merely abstracts from life to produce a harmonious pattern of its own.