Adrift on an Ice-Pan

It was scarcely safe to move on my small ice raft for fear of breaking it. Yet I saw I must have the skins of some of my dogs—of which I had eight on the pan—if I was to live the night out. There were now some three to five miles between me and the north side of the bay. There, immense pans of Arctic ice, surging to and fro on the heavy ground seas, were thundering into the cliffs like medieval battering rams. It was evident that, even if seen, I could hope for no help from that quarter before night. No boat could live through the surf.

Unwinding the sealskin traces from my waist, round which I had wound them to keep the dogs from eating them, I made a slip-knot, passed it over the first dog’s head, tied it around my foot close to his neck, threw him on his back, and stabbed him in the heart. Poor beast! I loved him like a friend—a beautiful dog—but we could not all hope to live. I had no hope any of us would at that time, but it seemed better to die fighting.

Despite my care, the struggling dog bit me rather severely in the leg. I suppose my numb hands prevented my holding his throat as I could ordinarily do. Moreover, I must have the knife in the wound to the end, as blood on the fur would freeze solid and make the skin useless. In this way, I sacrificed two more large dogs, receiving only one more bite, though I fully expected that the pan I was on would break up in the struggle. The other dogs, who were licking their coats and trying to get dry, apparently took no notice of the fate of their comrades—but I was cautious to prevent the dying dogs from crying out, for the noise of fighting would probably have been followed by the rest attacking the down dog, and that was too close to me to be pleasant. A short shrift seemed better than a long one, and I envied the dead dogs whose troubles were over so quickly. Indeed, I came to balance in my mind whether, once I passed into the open sea, it would not be better by far to use my faithful knife on myself than to die by inches. There seemed no hardship in the thought. I seemed entirely to sympathize with the Japanese view of hara-kiri.

Working, however, saved me from philosophizing. By the time I had skinned these dogs and strung the skins together with my knife and some of the harness, I was ten miles on my way, and it was getting dark.

Read or download Book

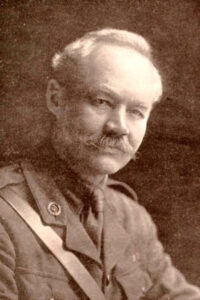

Sir Grenfell Wilfred Thomason

Sir Wilfred Thomason Grenfell KCMG (28 February 1865 – 9 October 1940) was a British medical missionary to Newfoundland who wrote books on his work and other topics.

Biography.

He was born at Parkgate, Cheshire, England, on 28 February 1865, the Son of Rev. Algernon Sidney Grenfell, headmaster of Mostyn House School, and Jane Georgiana Hutchison.

Grenfell moved to London in 1882. He then commenced his studies in medicine at the London Hospital Medical College (now part of Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry) under the tutelage of Sir Frederick Treves. He graduated in 1888.

Career

The Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen sent Grenfell to Newfoundland in 1892 to improve the plight of coastal inhabitants and fishermen. That mission began in earnest in 1892 when he recruited two nurses and two doctors for hospitals at Indian Harbour, Labrador and later opened cottage hospitals along the coast of Labrador. The mission expanded considerably from its initial mandate to one of developing schools, an orphanage, cooperatives, industrial work projects, and social work. Although founded to serve the local area, the mission expanded to include the aboriginal peoples and settlers along the coasts of Labrador and the eastern side of the Great Northern Peninsula of western Newfoundland. One of the children Grenfell assisted was an Inuit girl, Kirkina, for whom he helped secure artificial limbs, and later, the Grenfell Mission educated her in nursing and midwifery.

In 1907, Grenfell imported a group of 300 reindeer from Norway to provide food and serve as draft animals in Newfoundland. Unbeknownst to him, some animals carried a parasitic roundworm, Elaphostrongylus rangiferi, that spread to native caribou herds. The reindeer herd eventually disappeared; however, the parasite took hold and caused cerebrospinal elaphostrongylosis (CSE) in caribou, a disease well-known in reindeer in Scandinavia.

In 1908, Grenfell was on his way with his dogs to a Newfoundland village for a medical emergency when he got caught in “slob”, from which he got onto an ice pan with the dogs. He was forced to sacrifice some of his dogs to make a warm fur coat for himself. After drifting for several days without food or fresh water, he was rescued by some villagers in the area. Because of this experience, he buried the dogs and put up a plaque saying, “Who gave their lives for me.”

By 1914, the mission had gained international status. To manage its property and affairs, the International Grenfell Association, a non-profit mission society, was founded to support Grenfell’s work. The Association operated until 1981 as an NGO. It was responsible for delivering healthcare and social services in northern Newfoundland and Labrador. After 1981 a governmental agency, The Grenfell Regional Health Services Board took over the operational responsibility. The International Grenfell Association, having divested itself of all properties and operational responsibility for health and social services, boarding schools and hospitals, became a supporting association making grants and funding scholarships for medical training.

For his years of service on behalf of the people of these communities, the King knighted him in 1927.

In 1931, Grenfell had a small speaking role in The Viking, in which he narrated the film’s prologue and briefly stated the tragic circumstances involving the film’s production. During the film’s production, which was filmed on location in Newfoundland, producer Varick Frissell felt that the film needed more action sequences and set out on the ice floes to film them. During filming, the ship, SS Viking, on which filming was taking place, exploded, killing Frissell and 27 others.