An Outline of Occult Science

Two things present themselves for consideration. First, no human being will, on deeper reflection, be able in the long run to shut his eyes to the fact that his most important questions as to the meaning and significance of life must remain unanswered, if there be no access to higher worlds. Theoretically, we may delude ourselves concerning this fact and so get away from it; the depths of our soul-life, however, will not tolerate such self-delusion. The person who will not listen to what comes from [pg xii] these depths of the soul will naturally reject any account of supersensible worlds. There are however people—and their number is not small—who find it impossible to remain deaf to the demands coming from the depths of the soul. They must always be knocking at the gates which, in the opinion of others, bar the way to what is “incomprehensible.”

Secondly, the statements of “exact thinkers” are on no account to be despised. Where they have to be taken seriously, one who occupies himself with them will thoroughly feel and appreciate this seriousness. The writer of this book would not like to be taken for one who lightly disregards the enormous thought labor that has been expended in determining the limits of the human intellect. This thought labor cannot be put aside with a few phrases about “academic wisdom” and the like. In many cases, it has its source in true striving after knowledge and in genuine discernment. Indeed, even more than this must be admitted; reasons have been brought forward to show that that knowledge is today regarded as scientific cannot penetrate supersensible worlds, and these reasons are in a certain sense irrefutable.

Now it may appear strange to many people that the writer of this book admits this freely, and yet undertakes to make statements about supersensible worlds. It seems indeed almost impossible that a person should admit in a certain sense the reasons [pg xiii] why knowledge of superphysical worlds is unattainable, and should yet speak about those worlds.

Yet it is possible to take this attitude, and at the same time to understand that it impresses others as being inconsistent. It is not given to everyone to enter into the experiences we pass through when we approach supersensible realms with the human intellect. Then it turns out that intellectual proofs may certainly be irrefutable, and that notwithstanding this, they need not be decisive about reality. Instead of all sorts of theoretical explanations, let us now try to make this comprehensible by a comparison. That comparisons are not in themselves proofs is readily admitted, but this does not prevent them often making intelligible what has to be expressed.

Read or download Book

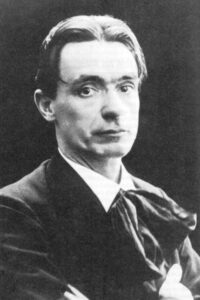

Rudolph Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century as a literary critic and published works including The Philosophy of Freedom. At the beginning of the twentieth century he founded an esoteric spiritual movement, anthroposophy, with roots in German idealist philosophy and theosophy. His teachings are influenced by Christian Gnosticism (for heresiologists there is little doubt that these are neognosticism). Many of his ideas are pseudoscientific. He was also prone to pseudohistory.

In the first, more philosophically oriented phase of this movement, Steiner attempted to find a synthesis between science and spirituality. His philosophical work of these years, which he termed “spiritual science”, sought to apply what he saw as the clarity of thinking characteristic of Western philosophy to spiritual questions, differentiating this approach from what he considered to be vaguer approaches to mysticism. In a second phase, beginning around 1907, he began working collaboratively in a variety of artistic media, including drama, dance, and architecture, culminating in the building of the Goetheanum, a cultural center to house all the arts. In the third phase of his work, beginning after World War I, Steiner worked on various ostensibly applied projects, including Waldorf education, biodynamic agriculture, and anthroposophical medicine.

Steiner advocated a form of ethical individualism, to which he later brought a more explicitly spiritual approach. He based his epistemology on Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s worldview (who, in turn, was influenced by Emanuel Swedenborg), in which “thinking…is no more and no less an organ of perception than the eye or ear. Just as the eye perceives colors and the ear sounds, so thinking perceives ideas.” A consistent thread that runs through his work is the goal of demonstrating that there are no limits to human knowledge.

Biography

Steiner’s father, Johann(es) Steiner (1829–1910), left a position as a gamekeeper in the service of Count Hoyos in Geras, northeast Lower Austria to marry one of the Hoyos family’s housemaids, Franziska Blie (1834 Horn – 1918, Horn), a marriage for which the Count had refused his permission. Johann became a telegraph operator on the Southern Austrian Railway, and at the time of Rudolf’s birth was stationed in Murakirály (Kraljevec) in the Muraköz region of the Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire (present-day Donji Kraljevec in the Međimurje region of northernmost Croatia). In the first two years of Rudolf’s life, the family moved twice, first to Mödling, near Vienna, and then, through the promotion of his father to the stationmaster, to Pottschach, located in the foothills of the eastern Austrian Alps in Lower Austria.

Steiner entered the village school, but following a disagreement between his father and the schoolmaster, he was briefly educated at home. In 1869, when Steiner was eight years old, the family moved to the village of Neudörfl, and in October 1872 Steiner proceeded from the village school there to the realschule in Wiener Neustadt.

In 1879, the family moved to Inzersdorf to enable Steiner to attend the Vienna Institute of Technology, where he enrolled in courses in mathematics, physics, chemistry, botany, zoology, and mineralogy and audited courses in literature and philosophy, on an academic scholarship from 1879 to 1883, where he completed his studies and the requirements of the Ghega scholarship satisfactorily. In 1882, one of Steiner’s teachers, Karl Julius Schröer, 3 suggested Steiner’s name to Joseph Kürschner, chief editor of a new edition of Goethe’s works, who asked Steiner to become the edition’s natural science editor, a truly astonishing opportunity for a young student without any form of academic credentials or previous publications.

Before attending the Vienna Institute of Technology, Steiner had studied Kant, Fichte, and Schelling.