Dwellers in the Hills

The slim buckskin lash would dart out hissing, writhe an instant on the hammered roadbed, and snap back with a sharp, clear report.

The great sorrel was oblivious to this pastime of his master. The lash whistled narrowly by his red ears, but it never touched them. In the evening sunlight, the Cardinal was a horse of bronze.

Opposite me in the shadow of the tall hickory timber the man Ump, doubled like a finger, was feeling tenderly over the coffin joints and the steel blue hoofs of the Bay Eagle, blowing away the dust from the clinch of each shoe nail and pressing the flat calks with his thumb. No mother ever explored with more loving care the mouth of her child for evidence of a coming tooth. Ump was on his never-ending quest for the loose shoe nail. It was the serious business of his life.

I think he loved this trim, nervous mare better than any other thing in the world. When he rode, perched like a monkey, with his thin legs held close to her sides, and his short, humped back doubled over, and his head with its long hair bobbing about as though his neck were loose-coupled somehow, he was eternally caressing her mighty withers, or feeling for the play of each iron tendon under her satin skin. And when we stopped, he glided down to finger her shoe-nails.

Then he talked to the mare sometimes, as he was doing now. “There is a little ridge in the hoof, girl, but it won’t crack; I know it won’t crack.” And, “This nail is too high. It is my fault. I was gabbin’ when old Hornick drove it.”

On his feet, he looked like a clothespin with the face of the strangest old child. He might have been one left from the race of Dwarfs who, tradition said, lived in the Hills before we came.

His mare was the mother of El Mahdi. I remember how Ump cried when the colt was born, and how he sat out in the rain, a miserable drenched rat, because his dear Bay Eagle was in the mysterious troubles of maternity, and because she must be very unhappy at being on the north side of the hill among the black hawthorn bushes, for that was a bad sign—the worst sign in the world—showing the devil would have his day with the colt now and then.

I used, when I was little, to hear talk once in a while of some very wonderful person whom men called a “genius,” and of what it was to be a genius. The word puzzled me a good deal because I could not understand what was meant when it was explained to me.

Read or download Book

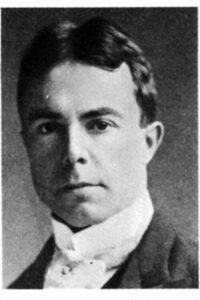

Melville Davisson Post

Melville Davisson Post (April 19, 1869 – June 23, 1930) was an American writer, born in Harrison County, West Virginia. Although his name is not immediately familiar to those outside of specialist circles, many of his collections are still in print, and many collections of detective fiction include works by him. Post’s best-known character is the mystery-solving, justice-dispensing West Virginian backwoodsman, Uncle Abner. The 22 Uncle Abner tales, written between 1911 and 1928, have been called some of “the finest mysteries ever written”.

Post’s other recurring characters include the lawyers Randolph Mason and Colonel Braxton, and the detectives Sir Henry Marquis and Monsieur Jonquelle. His total output was approximately 230 titles, including several non-crime novels.

Biography

Post was born on 19 April 1869 in Harrison County, West Virginia, the son of Ira Carper Post, a wealthy farmer; his mother was Florence May (née Davisson). Post’s family had settled in the Clarksburg, West Virginia area in the late 18th century.

Career

Post earned a law degree from West Virginia University in 1892 and was elected the same year as the youngest member of the Electoral College. He practiced law with a firm in Wheeling, West Virginia but became uninterested in politics, instead concentrating on writing.[6] His first published Uncle Abner story was in 1911, and they appeared in newspapers throughout the country. His collection of Uncle Abner stories was first printed in 1918 and remained in print (at its original price) for two decades, which Craig Johnson believes made him the highest-paid and most commercially published author of that time. Collier Books reprinted the stories in 1962 and the University of California Press in 1974.

Personal life

In 1903, he married Ann Bloomfield Gamble Schofield. Their only child (a son, Ira) died in infancy, after which Melville and Ann traveled to Europe. They later owned and managed a stable for polo ponies. Ann died of pneumonia in 1919.

Death

Post, an avid horseman, died on June 23, 1930, after falling from his horse at age 61. He had published 230 titles, most of them crime fiction. He is buried in Elkview Masonic Cemetery in Harrison County.

Legacy

Post’s boyhood home, “Templemoor”, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

Fiction

Post wrote three volumes of stories about Randolph Mason, a brusque New York lawyer who is highly skilled at turning legal loopholes and technicalities to his client’s advantage.

In the first two volumes (The Strange Schemes of Randolph Mason and The Man of Last Resort, published 1896–1897), Mason is depicted as an utterly amoral character who advises criminals how to commit wrongdoings without breaking the letter of the law. The best-known of these stories is “The Corpus Delicti”, in which Mason’s client murders a blackmailing lover and dissolves her dismembered corpse in acid. Despite overwhelming circumstantial evidence, Mason secures his client’s acquittal because no body has been found and there are no eyewitnesses to the woman’s death. (New York law at the time allowed one of these two conditions to be established by circumstantial evidence, but not both.) Post deflected criticism of such sensational stories by declaring that he was publicly exposing weaknesses in the law that needed to be rectified. Nevertheless, in a third volume (1908’s The Corrector of Destinies), Mason had become a reformed man who used his knowledge of the law for more beneficent purposes. Post explained Mason’s change of character by stating the lawyer had been suffering from mental illness in the two earlier volumes.