Real Ghost Stories

Many people will object—some have already objected—to the subject of this book. It is an offense to some to take a ghost too seriously; to others, it is a still greater offense not to take ghosts seriously enough. One set of objections can be paired off against the other; neither objection has a very solid foundation. The time has surely come when the fair claim of ghosts to the impartial attention and careful observation of mankind should no longer be ignored. In earlier times people believed in them so much that they cut their acquaintance; in later times people believe in them so little that they will not even admit their existence. Thus these mysterious visitants have hitherto failed to enter into that friendly relationship with mankind that many of them seem sincerely to desire.

But what with the superstitious credulity of one age and the equally superstitious unbelief of another, it is necessary to begin from the beginning and convince a skeptical world that apparitions appear. To do this it is necessary to insist that your ghost should no longer be ignored as a phenomenon of Nature. He has a right, equal to that of any other natural phenomenon, to be examined observed, studied, and defined. He is indeed a rather difficult phenomenon; his comings and goings are rather intermittent and fitful, his substance is too shadowy to be handled, and he has avoided hitherto equally the obtrusive inquisitiveness of the microscope and telescope.

A phenomenon that you can neither handle nor weigh, analyze nor dissect, is naturally regarded as intractable and troublesome; nevertheless, however intractable and troublesome he may be to reduce to any of the existing scientific categories, we have no right to allow his idiosyncrasies to deprive him of his innate right to be regarded as a phenomenon. As such he will be treated in the following pages, with all the respect due to phenomena whose reality is attested by a sufficient number of witnesses. There will be no attempt in this book to build up a theory of apparitions or to define the true inwardness of a ghost.

Read or download Book

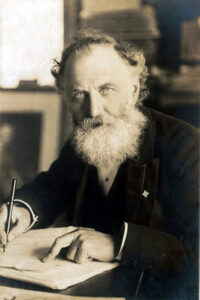

William Thomas Stead

William Thomas Stead (5 July 1849 – 15 April 1912) was an English newspaper editor who, as a pioneer of investigative journalism, became a controversial figure of the Victorian era. Stead published a series of hugely influential campaigns whilst editor of The Pall Mall Gazette, including his 1885 series of articles, The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon. These were written in support of a bill, later dubbed the “Stead Act”, that raised the age of consent from 13 to 16.

Stead’s “new journalism” paved the way for the modern tabloid in Great Britain. He has been described as “the most famous journalist in the British Empire”. He is considered to have influenced how the press could be used to influence public opinion and government policy, and advocated “Government by Journalism”. He was known for his reportage on child welfare, social legislation, and the reformation of England’s criminal codes.

Stead died in the sinking of the RMS Titanic.

Early life

Stead was born in Embleton, Northumberland on July 5, 1849, the son of the Reverend William Stead, a poor and respected Congregational minister, and Isabella (née Jobson), a cultivated daughter of a Northumberland farmer, John Jobson of Warkworth. A year later the family moved to Howdon on the River Tyne, where his younger brother, Francis Herbert Stead, was born. Stead was largely educated at home by his father, and by the age of five, he was already well-versed in the Holy Scriptures and is said to have been able to read Latin almost as well as he could read English. It was Stead’s mother who perhaps had the most lasting influence on her son’s career. One of Stead’s favorite childhood memories was of his mother leading a local campaign against the government’s controversial Contagious Diseases Acts – which required prostitutes living in garrison towns to undergo medical examination.

From 1862 to 1864, he attended Silcoates School in Wakefield until he was apprenticed to a merchant’s office on the Quayside in Newcastle upon Tyne, where he became a clerk.