The Body-Snatcher

One afternoon, when his day’s work was over, Fettes dropped into a famous tavern and found Macfarlane sitting with a stranger. This was a tiny man, ashen and dark, with coal-black eyes. The cut of his features gave a promise of intellect and refinement, which was but feebly realized in his manners, for he proved, upon a nearer acquaintance, coarse, vulgar, and stupid. He exercised, however, very remarkable control over Macfarlane, issued orders like the Great Bashaw, became inflamed at the most minor discussion or delay, and commented rudely on the servility with which he was obeyed. This most offensive person took a fancy to Fettes on the spot, plied him with drinks, and honoured him with unusual confidences on his past career. If a tenth part of what he confessed were genuine, he was a loathsome rogue, and the lad’s vanity was tickled by the attention of so experienced a man.

‘I’m a pretty bad fellow myself,’ the stranger remarked, ‘but Macfarlane is the boy – Toddy Macfarlane, I call him. Toddy, order your friend another glass.’ Or it might be, ‘Toddy, you jump up and shut the door.’ ‘Toddy hates me,’ he said again. ‘Oh, yes, Toddy, you do!’

‘Don’t you call me that confounded name,’ growled Macfarlane.

Read or download Book

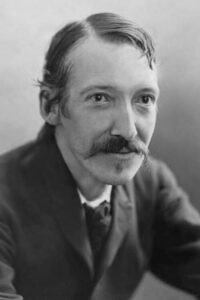

Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as Treasure Island, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Kidnapped and A Child’s Garden of Verses.

Biography.

Born and educated in Edinburgh, Stevenson suffered from serious bronchial trouble for much of his life but continued to write prolifically and travel widely in defiance of his poor health. As a young man, he mixed in London literary circles, receiving encouragement from Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse, Leslie Stephen and W. E. Henley, the last of whom may have provided the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island. In 1890, he settled in Samoa, where, alarmed at increasing European and American influence in the South Sea islands, his writing turned from romance and adventure fiction toward a darker realism. He died of a stroke in his island home in 1894 at age 44.

A celebrity in his lifetime, Stevenson’s critical reputation has fluctuated since his death, though his works are today generally acclaimed. In 2018, he was ranked just behind Charles Dickens as the 26th-most-translated author in the world.

Early writing and travels

Stevenson was soon active in London literary life, becoming acquainted with many of the writers of the time, including Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse and Leslie Stephen, the editor of The Cornhill Magazine, who took an interest in Stevenson’s work. Stephen took Stevenson to visit a patient at the Edinburgh Infirmary named William Ernest Henley, an energetic and talkative poet with a wooden leg. Henley became a close friend and occasional literary collaborator until a quarrel broke up the friendship in 1888, and he is often considered to be the inspiration for Long John Silver in Treasure Island.

Stevenson was sent to Menton on the French Riviera in November 1873 to recuperate after his health failed. He returned to better health in April 1874 and settled down to his studies, but he returned to France several times after that. He made long and frequent trips to the neighbourhood of the Forest of Fontainebleau, staying at Barbizon, Grez-sur-Loing and Nemours and becoming a member of the artists’ colonies there. He also travelled to Paris to visit galleries and theatres. He qualified for the Scottish bar in July 1875, aged 24, and his father added a brass plate to the Heriot Row house reading “R.L. Stevenson, Advocate”. His law studies did influence his books, but he never practised law; all his energies were spent on travel and writing. One of his journeys was a canoe voyage in Belgium and France with Sir Walter Simpson, a friend from the Speculative Society, a frequent travel companion, and the author of The Art of Golf (1887). This trip was the basis of his first travel book, An Inland Voyage (1878).

Reflections on the art of writing

Stevenson’s critical essays on literature contain “few sustained analyses of style or content”. In “A Penny Plain and Two-pence Coloured” (1884), he suggests that his approach owed much to the exaggerated and romantic world that, as a child, he had entered as proud owner of Skelt’s Juvenile Drama—a toy set of cardboard characters who were actors in melodramatic dramas. “A Gossip on Romance” (1882) and “A Gossip on a Novel of Dumas’s” (1887) imply that it is better to entertain than to instruct.

Stevenson saw himself very much in the mould of Sir Walter Scott, a storyteller who could transport his readers away from themselves and their circumstances. He took issue with what he saw as the tendency in French realism to dwell on sordidness and ugliness. In “The Lantern-Bearer” (1888), he appears to take Emile Zola to task for failing to seek out nobility in his protagonists.

In “A Humble Remonstrance”, Stevenson answers Henry James’s claim in “The Art of Fiction” (1884) that the novel competes with life. Stevenson protests that no book can ever hope to match life’s complexity; it merely abstracts from life to produce a harmonious pattern.