The Lust of Hate

In its customary fashion, ill luck pursued me when I set foot on Australian soil. I landed in Melbourne at a miserable time and, within a month, had lost half my capital in a plausible but ultimately unprofitable mining venture. The balance I took with me into the bush, only to lose it there as quickly as I had done the first in town. The aspect of affairs then changed completely. The so-called friends I had hitherto made deserted me with but one exception. That one, however, curiously enough, the least respectable of the lot, exerted himself on my behalf to such good purpose that he obtained the position of storekeeper on a Murrumbidgee sheep station.

I embraced the opportunity with enthusiasm and, for eighteen months, continued in the same employment, working with a certain amount of pleasure to myself and, I believe, some satisfaction to my employers. How long I should have remained there, I cannot say, but when the Banyah Creek goldfield was proclaimed, I caught the fever, abandoned my employment, and started, with my swag upon my back, to try my fortune. This turned out so poorly that less than seven weeks found me desperate, my savings departed, and my claim—which I must honestly confess showed but minor prospects of success—seized for a debt by a rascally Jew storekeeper upon the Field. A month later, a new rush swept away the inhabitants, and Banyah Creek was deserted.

Not wishing to be left behind, I followed the general inclination and, in something under a fortnight, was prostrated at death’s door by an attack of fever, to which I should probably have succumbed had it not been for the kindness of a misanthrope of the field, an old miner, Ben Garman by name. This extraordinary individual, who had tried his luck on every gold field of importance in the five colonies and was as yet as far off making his fortune as when he had first taken a shovel in his hand, found me lying unconscious alongside the creek.

He carried me to his tent and, neglecting his claim, set to work to nurse me back to life again. It was not until I had turned the corner and was convalescent that I discovered the curiosity my benefactor was. His appearance was as peculiar as his mode of life. He was very short, broad, and red-faced, wore a long grey beard, bristling white eyebrows, enormous ears, and the most extensive hands and feet I have ever seen on a human being. Where he had hailed from initially, he was unable to say. His earliest recollection was playing with another small boy upon the beach of one of the innumerable bays of Sydney harbour, but how he had got there, whether his parents had just emigrated or whether they had been out long enough for him to have been born in the colony were points of which he pronounced himself entirely ignorant.

Read or download Book

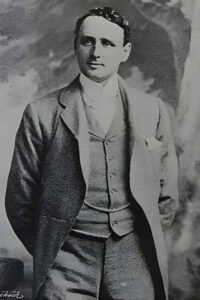

Guy Newell Boothby

Guy Newell Boothby (13 October 1867 – 26 February 1905) was a prolific Australian novelist and writer, noted for sensational fiction in variety magazines around the end of the nineteenth century. He lived mainly in England. He is best known for such works as the Dr Nikola series, about an occultist criminal mastermind who is a Victorian forerunner to Fu Manchu, and Pharos, the Egyptian, a tale of Gothic Egypt, mummies’ curses, and supernatural revenge. Rudyard Kipling was his friend and mentor, and his books were remembered with affection by George Orwell.

Biography

Boothby was born in Adelaide to a prominent family in the recently established British colony of South Australia. His father was Thomas Wilde Boothby, who for a time was a member of the South Australian Legislative Assembly, three of his uncles were senior colonial administrators, and his grandfather was Benjamin Boothby (1803–1868), controversial judge of the Supreme Court of South Australia from 1853 to 1867. When Boothby was aged approximately seven his English-born mother, whom he held in great regard, separated from his father and returned with her children to England. There he received a traditional English grammar school education at Salisbury, Lord Weymouth’s Grammar (now Warminster School), and Christ’s Hospital, London.

Following this, Boothby returned alone to South Australia at 16, where, in his turn, he entered the colonial administration as private secretary to the mayor of Adelaide, Lewis Cohen, but was “not contented” with the work. Despite Boothby’s family tradition of colonial service, his natural inclinations ran more to the creative than to the administrative and he was not satisfied with his limited role as a provincial colonial servant. In 1890, aged 23, Boothby wrote the libretto for Sylvia, a comic opera, published and produced at Adelaide in December 1890, and in 1891 his second show, The Jonquil: an Opera, appeared. He also wrote and performed in an operetta, Dimple’s Lovers, for Adelaide’s Garrick Club theatre group. The music in each case was written by Cecil James Sharp. His early literary ventures were directed at the theatre, but his ambition was not appeased by the lukewarm response his melodramas received in Adelaide. When severe economic collapse hit most of the Australian colonies in the early 1890s, he followed the well-beaten path to London in December 1891.

Boothby, however, was thwarted in his first bid for recognition as lack of funds forced him to disembark en route in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and begin making his way homewards through South East Asia. According to family legend, the dire poverty he faced on this journey led him to accept any kind of work he could get: ‘This meant working before the mast, stoking in ocean tramps, attending in a Chinese opium den in Singapore, digging in the Burmah Ruby fields, acting, prize fighting, cow punching…’ This was followed by a brief sojourn on Thursday Island, a Melanesian island in the Torres Strait group recently annexed by the Queensland colony, where he worked as a diver in the lucrative pearl trade; and finally by an arduous journey overland across the Australian continent home to Adelaide. While Depasquale, author of the only Boothby biography, warns that this account of his travels may be somewhat glamorous, Boothby certainly traveled extensively in South East Asia, Melanesia, and Australia during this period, collecting a stock of colonial anecdotes and experiences that were to influence much of his later writing.

Approximately two years later, Boothby finally reached London and succeeded in having an account of his peregrinations, On the Wallaby, or Through the East and Across Australia, published in 1894. The travelogue met with reasonable success, which was matched later that year by Boothby’s first novel, In Strange Company. A novel of adventure set variously in England, Australia, the South Seas, and South America, In Strange Company established a pattern that was to characterize the succeeding Boothby oeuvre – the use of exotic, international, and particularly Australasian locales that frequently function as an end in themselves superfluous to the requirements of the plot. By October 1895, Boothby had completed three further novels, including A Bid for Fortune, the first Dr Nikola novel which catapulted Boothby to wide acclaim. Of the two other novels Boothby wrote in 1895 A Lost Endeavour was set on Thursday Island and The Marriage of Esther ranged across several Torres Strait Islands. Boothby continued to produce fiction at a ferocious rate, producing up to six novels a year across the range of genres prevalent at the fin de siècle and is credited with producing over 53 novels in total, not to mention dozens of short stories and plays.