The Man-Eaters of Tsavo and Other East African Adventures

There were four men on board, all nearly dead from thirst; they had been without drink of any kind for several days and had completely lost their bearings. After giving them some casks of water, we directed them to Muscat (the port they wished to make), and our vessel resumed its journey, leaving them still becalmed amid that glassy sea. Whether they managed to reach their destination I never knew.

As our steamer made its way to its anchorage, the romantic surroundings of the harbor of Mombasa conjured up, visions of stirring adventures of the past, and recalled to my mind the many tales of reckless doings of pirates and slavers, which as a boy it had been my delight to read. I remembered that it was at this very place that in 1498 the great Vasco da Gama nearly lost his ship and life through the treachery of his Arab pilot, who plotted to wreck the vessel on the reef which bars more than half the entrance to the harbor. Luckily, this nefarious design was discovered in time, and the bold navigator promptly hanged the pilot, and would also have sacked the town but for the timely submission and apologies of the Sultan. In the principal street of Mombasa — appropriately called Vasco da Gama Street — there still stands a curiously shaped pillar which is said to have been erected by this great seaman in commemoration of his visit.

Scarcely had the anchor been dropped, when, as if by magic, our vessel was surrounded by a fleet of small boats and “dug-outs” manned by crowds of shouting and gesticulating natives. After a short fight between some rival Swahili boatmen for my baggage and person, I found myself being vigorously rowed to the foot of the landing steps by the bahareen (sailors) who had been successful in the encounter. Now, my object in coming out to East Africa at this time was to take up a position to which I had been appointed by the Foreign Office on the construction staff of the Uganda Railway.

As soon as I landed, therefore, I enquired from one of the Customs officials where the headquarters of the railway were to be found and was told that they were at a place called Kilindini, some three miles away, on the other side of the island. The best way to get there, I was further informed, was by gharri, which I found to be a small trolley, having two seats placed back to back under a little canopy and running on narrow rails which are laid through the principal street of the town.

Read or download Book

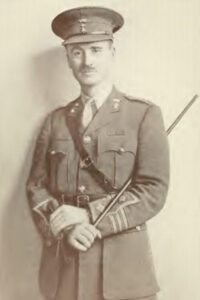

John Henry Patterson

Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson DSO (10 November 1867 – 18 June 1947) was an Anglo-Irish military officer, hunter, and author best known for his book The Man-eaters of Tsavo (1907), which details Patterson’s experiences during the construction of a railway bridge over the Tsavo River in the East Africa Protectorate from 1898 to 1899. The book went on to inspire three films: Bwana Devil (1952), Killers of Kilimanjaro (1959), and The Ghost and the Darkness (1996). During World War I, Patterson served as the commander of the British Army’s Jewish Legion, which has been described as the first precursor to the Israel Defense Forces.

Biography

Youth and Army service

Patterson was born in 1867 in Forgney, Ballymahon, County Longford, Ireland, to a Protestant father and a Roman Catholic mother. He joined the British Army in 1885 at the age of seventeen and eventually attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO). He retired from the army in 1920.

East African adventures

In 1898, Patterson was commissioned by the Uganda Railway Committee in London to oversee the construction of a railway bridge over the Tsavo River in present-day Kenya. He arrived at the site in March of that year.

Tsavo railway and man-eaters

Main article: Tsavo Man-Eaters

Almost immediately after Patterson’s arrival, lion attacks began to take place on the workforce, with the lions dragging men out of their tents at night and feeding on their victims. Despite the building of thorn barriers (bomas) around the camps, bonfires at night, and strict after-dark curfews, the attacks escalated dramatically, to the point where the bridge construction ceased due to a fearful, mass departure by the workers. Along with the obvious financial consequences of the work stoppage, Patterson faced the challenge of maintaining his authority and even his safety at this remote site against the increasingly hostile and superstitious workers, many of whom were convinced that the lions were evil spirits, come to punish those who worked at Tsavo, and that he was the cause of the misfortune because the attacks had coincided with his arrival.

The man-eating behavior was considered highly unusual for lions and was eventually confirmed to be the work of a pair of rogue males, who were believed to be responsible for as many as 140 deaths. Railway records attribute only 28 worker deaths to the lions, but the predators were also reported to have killed a significant number of local people of which no official record was ever kept, which attributed to the railway’s smaller record.