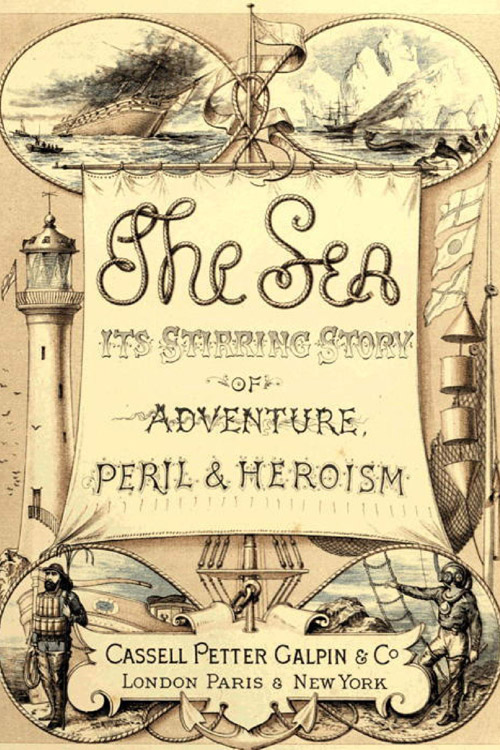

The Sea Is a Stirring Story of Adventure, Peril, & Heroism. Volume 1

And though this is the exaggerated and not strictly accurate language of poetry, we may, with Pollok, fairly address the great sea as the “strongest of creation’s sons.” The first impressions produced on most animals—not excluding altogether man—by the aspect of the ocean are of terror to a greater or lesser degree. Livingstone tells us that he had intended to bring a friendly native from Africa to England, a man as courageous as the lion he had often braved.

He had never voyaged upon nor even beheld the sea, and on board the ship which would have safely borne him to a friendly shore, he became delirious and insane. Though assured of safety and carefully watched, he escaped one day and blindly threw himself headlong into the waves. The sea terrified him and held and drew him, fascinated as under a spell. “Even at ebb-tide,” says Michelet,3 “when, placid and weary, the wave crawls softly on the sand, the horse does not recover his courage. He trembles and frequently refuses to pass the languishing ripple. The dog barks and recoils and, according to his manner, insults the billows which he fears….

A traveller tells us that the dogs of Kamtschatka, though accustomed to the spectacle, are not the less terrified and irritated by it. In numerous troops, they howl through the protracted night against the howling waves and endeavour to outvie the Ocean of the North in a fury.” The civilized man’s fear is founded, it must be admitted, on a reasonable knowledge of the ocean, so much his friend and yet so often his foe. Man is not independent of his fellow man in distant countries, nor is it desirable that he should be. No land produces all the necessities and luxuries that have begun to be considered necessary and sufficient for themselves.

Transportation by land is often impracticable or too costly, and the ocean thus becomes the great highway of nations. Vessel after vessel, fleet after fleet, arrive safely and speedily. But as there is danger for man lurking everywhere on land, so also is there on the sea. As we shall see hereafter, the world’s wreck chart for one year must be appalling. That for the British Empire alone in one year has often exceeded 1,000 vessels, great and small! Averaging three years, we find an annual loss of 1,095 vessels and 1,952 lives during that period.4 Nor are the ravages of ocean confined to the engulfment of vessels, from rotten “coffin-ships” to splendid ironclads. The coasts often bear witness to her fury.

Read or download Book

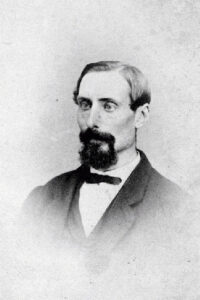

Frederick Whymper

Whymper was the eldest son of Elizabeth Whitworth Claridge and Josiah Wood Whymper, a celebrated wood engraver and artist.

Biography.

His younger brother, Edward Whymper, was a renowned alpinist who made the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865. In his youth, Whymper was a talented artist who worked to produce engravings for publication and had his landscapes on exhibit at the Royal Academy of Arts in London from 1859 to 1861. He travelled to Victoria, British Columbia, in 1862 and the Cariboo the following year.

In 1864, he joined road builders in Bute Inlet on the Pacific Coast, leaving shortly before the Chilcotin War. 10 Many of his early travels were by steamship; his drawings include volcanoes on Kamchatka and Alaskan glaciers. While in the far north, Whymper served on the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition and the Western Union Telegraph Expedition (1865), spending the winter of 1866 at Nulato, Alaska with W.H. Dall and traveling up the Yukon River to Fort Yukon, where he witnessed the first American flag being raised over the new territory of Alaska.

In November 1867, Whymper arrived back in England, where his account of his travels, Travel and Adventure in the Territory of Alaska, was published in 1868. In 1869, he went back to the United States, by way of New York City to San Francisco, and worked on the staff of the newspaper Alta California. City directories describe him as an artist and mining engineer, and in 1871, he was a founding member of the San Francisco Art Association.

He returned to England at some point, publishing The Heroes of the Arctic and their Adventures and The Sea: Its Stirring Story of Adventure, Peril, and Heroism, before he died in London on 26 November 1901 by what is listed as “failure of the heart, probably due to indigestion, arising from sedentary pursuits”, in his obituary. Mount Whymper, north of Lake Cowichan in British Columbia, is named in honour of the early explorer, artist, and writer. Another taller Mount Whymper in British Columbia is named after his brother Edward, who was the first to climb it.