The Viceroy’s Protégéor, A Prince of Swindlers

That it should have fallen to the lot of one who has always prided himself on steering clear of undesirable acquaintances to introduce to his friends one of the most notorious adventurers our capital has ever seen seems like the irony of fate. Perhaps, however, if I begin by showing how cleverly our meeting was contrived, those who would otherwise feel inclined to criticize me will pause before passing judgment and ask themselves whether they would not have walked into the snare as unsuspectingly as I did.

It was during the last year of my term of office as Viceroy, and while I was paying a visit to the Governor of Bombay, that I decided upon making a tour of the northern Provinces, beginning with Peshawur and winding up with the Maharajah of Malar-Kadir. As the latter potentate is so well known, I need not describe him. His forcible personality, his enlightened rule, and the progress his state has made within the last ten years are well known to every student of the history of our magnificent Indian Empire.

My stay with him was a pleasant finish to an otherwise monotonous business, for his hospitality has a worldwide reputation. When I arrived, he placed his palace, servants, and stables at my disposal just as I pleased. My time was practically my own. I could be as solitary as a hermit if I desired; however, I had to give the order, and five hundred men would cater for my amusement. It seems, therefore, the more unfortunate that to this pleasant arrangement, I should have to attribute the calamities, which is the purpose of this series of stories to narrate.

On the third morning of my stay, I woke early. When I had examined my watch, I discovered that it wanted an hour of daylight, and, not feeling inclined to go to sleep again, I wondered how I should employ my time until my servant should bring me my chota haze or early breakfast. On proceeding to my window, I found a perfect morning, the stars still shining, though, in the east, they were paling before the approach of dawn. It was challenging to realize that in a few hours, the earth, which now looked so excellent and wholesome, would lie, burnt up and quivering, beneath the blazing Indian sun.

I stood and watched the picture presented to me for some minutes until I had an overwhelming desire to order a horse and go for a long ride before the sun appeared above the jungle trees. The temptation was more than I could resist, so I crossed the room and, opening the door, woke my servant, sleeping in the antechamber.

Read or download Book

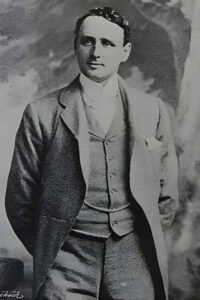

Guy Newell Boothby

Guy Newell Boothby (13 October 1867 – 26 February 1905) was a prolific Australian novelist and writer, noted for sensational fiction in variety magazines around the end of the nineteenth century. He lived mainly in England. He is best known for such works as the Dr Nikola series, about an occultist criminal mastermind who is a Victorian forerunner to Fu Manchu, and Pharos, the Egyptian, a tale of Gothic Egypt, mummies’ curses, and supernatural revenge. Rudyard Kipling was his friend and mentor, and his books were remembered with affection by George Orwell.

Biography

Boothby was born in Adelaide to a prominent family in the recently established British colony of South Australia. His father was Thomas Wilde Boothby, who for a time was a member of the South Australian Legislative Assembly, three of his uncles were senior colonial administrators, and his grandfather was Benjamin Boothby (1803–1868), controversial judge of the Supreme Court of South Australia from 1853 to 1867. When Boothby was aged approximately seven his English-born mother, whom he held in great regard, separated from his father and returned with her children to England. There he received a traditional English grammar school education at Salisbury, Lord Weymouth’s Grammar (now Warminster School), and Christ’s Hospital, London.

Following this, Boothby returned alone to South Australia at 16, where, in his turn, he entered the colonial administration as private secretary to the mayor of Adelaide, Lewis Cohen, but was “not contented” with the work. Despite Boothby’s family tradition of colonial service, his natural inclinations ran more to the creative than to the administrative and he was not satisfied with his limited role as a provincial colonial servant. In 1890, aged 23, Boothby wrote the libretto for Sylvia, a comic opera, published and produced at Adelaide in December 1890, and in 1891 his second show, The Jonquil: an Opera, appeared. He also wrote and performed in an operetta, Dimple’s Lovers, for Adelaide’s Garrick Club theatre group. The music in each case was written by Cecil James Sharp. His early literary ventures were directed at the theatre, but his ambition was not appeased by the lukewarm response his melodramas received in Adelaide. When severe economic collapse hit most of the Australian colonies in the early 1890s, he followed the well-beaten path to London in December 1891.

Boothby, however, was thwarted in his first bid for recognition as lack of funds forced him to disembark en route in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and begin making his way homewards through South East Asia. According to family legend, the dire poverty he faced on this journey led him to accept any kind of work he could get: ‘This meant working before the mast, stoking in ocean tramps, attending in a Chinese opium den in Singapore, digging in the Burmah Ruby fields, acting, prize fighting, cow punching…’ This was followed by a brief sojourn on Thursday Island, a Melanesian island in the Torres Strait group recently annexed by the Queensland colony, where he worked as a diver in the lucrative pearl trade; and finally by an arduous journey overland across the Australian continent home to Adelaide. While Depasquale, author of the only Boothby biography, warns that this account of his travels may be somewhat glamorous, Boothby certainly traveled extensively in South East Asia, Melanesia, and Australia during this period, collecting a stock of colonial anecdotes and experiences that were to influence much of his later writing.

Approximately two years later, Boothby finally reached London and succeeded in having an account of his peregrinations, On the Wallaby, or Through the East and Across Australia, published in 1894. The travelogue met with reasonable success, which was matched later that year by Boothby’s first novel, In Strange Company. A novel of adventure set variously in England, Australia, the South Seas, and South America, In Strange Company established a pattern that was to characterize the succeeding Boothby oeuvre – the use of exotic, international, and particularly Australasian locales that frequently function as an end in themselves superfluous to the requirements of the plot. By October 1895, Boothby had completed three further novels, including A Bid for Fortune, the first Dr Nikola novel which catapulted Boothby to wide acclaim. Of the two other novels Boothby wrote in 1895 A Lost Endeavour was set on Thursday Island and The Marriage of Esther ranged across several Torres Strait Islands. Boothby continued to produce fiction at a ferocious rate, producing up to six novels a year across the range of genres prevalent at the fin de siècle and is credited with producing over 53 novels in total, not to mention dozens of short stories and plays.