After The Storm

The party was in couples, and as Mr. Emerson had decided to go without his young wife, he had to ride alone. The absence of Irene was felt as a drawback to the company’s pleasure. Miss Carman, who understood the real cause of Irene’s refusal to ride, was so troubled in her mind that she sat almost silent during the two hours they were out. Mr. Emerson left the party after they had been out for an hour and returned to the hotel. His excitement had cooled off, and he began to regret the unbending way he had met his bride’s unhappy mood.

“Her over-sensitive mind has taken up a wrong impression,” he said, as he talked with himself, “and, instead of saying or doing anything to increase that impression, I should, by word and act of kindness, have done all in my power for its removal. Two wrongs never make a right. Passion results. Not in peace, meet passion. I should have soothed and yielded and so won her back to reason. I ought to possess a cooler and more rationally balanced mind as a man. She is a being of feeling and impulse—loving, ardent, proud, sensitive and strong-willed. Knowing this, it was madness in me to chafe instead of soothing her, to oppose, when gentle concession would have torn from her eyes an illusive veil. Oh, I could learn wisdom in time! I was in no ignorance as to her peculiar character. I knew her faults, weaknesses, and nobler qualities and wanted to stimulate the one and bear with the others. Duty, love, honour, humanity, all pointed to this.”

Read or download Book

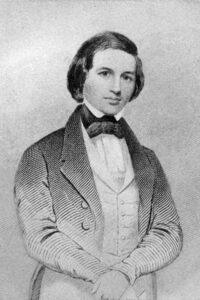

T. S. Arthur

Timothy Shay Arthur (June 6, 1809 – March 6, 1885), known as T. S. Arthur, was a popular 19th-century American author. He is famous for his temperance novels Ten Nights in a Bar-Room and What I Saw There (1854), which helped demonize alcohol in the eyes of the American public.

His stories, written with compassion and sensitivity, articulated and spread values and ideas associated with “respectable middle-class “ life in America. He also believed greatly in the transformative and restorative power of love, as shown in one of his stories, “An Angel in Disguise.”

He was also the author of dozens of stories for Godey’s Lady’s Book, the most famous American monthly magazine in the antebellum era, and he published and edited his own Arthur’s Home Magazine, a periodical in the Godey’s model, for many years. Virtually forgotten now, Arthur did much to articulate and disseminate the values, beliefs, and habits that defined respectable, proper middle-class life in America.

Biography

Arthur was born in Newburgh, New York, and was a child in Fort Montgomery, New York. By 1820, Arthur’s father, a miller, had relocated to Baltimore, Maryland, where Arthur briefly attended local schools. At age fourteen, Arthur apprenticed to a tailor, but poor eyesight and a general lack of aptitude for physical labour led him to seek other work. He then found employment with a wholesale merchandiser and later as an agent for an investment concern, a job that took him briefly to Louisville, Kentucky. Otherwise, he lived as a young adult in Baltimore.

Smitten by literature, Arthur devoted as much time as possible to reading and fledgling writing attempts. By 1830, he had begun to appear in local literary magazines. That year, he contributed poems under his name and pseudonyms to a gift book called The Amethyst. Also during this time, he participated in an informal literary coterie called the Seven Stars (the name was drawn from that of the tavern in which they met), whose members also included Edgar Allan Poe.

Professional success of T. S. Arthur

The 1830s saw Arthur mount several efforts to become a professional author and publisher. All failed, but collectively, they gave Arthur numerous chances to hone his craft. In 1838, he co-published The Baltimore Book, a gift book that included a short tale contributed by Poe called “Slope.” Toward the end of the decade, Arthur published in the brief format a novel called Insubordination that, in 1842, appeared in hardcover. In 1840, he wrote a series of newspaper articles on the Washingtonian Temperance Society, a local organization formed by working-class artisans and mechanics to counter the life-ruining effects of drink. The articles were widely reprinted and helped fuel the establishment of Washingtonian groups nationwide. Arthur’s newspaper sketches were collected in book form as Six Nights with the Washingtonians (1842). Six Nights went through many editions and helped establish Arthur in the public eye as an author associated with the temperance movement.

1840, Arthur also placed his first short tale in Godey’s Lady’s Book. Called “Tired of Housekeeping,” its subject is a middle-class family who struggles to supervise recalcitrant cooks and servants. Encouraged by his success, Arthur moved to Philadelphia in 1841 to be near the offices of America’s most popular home magazines. He continued to write tales for Godey’s and other periodicals. He issued collected editions of his tales and published novel-length narratives almost yearly. He also authored children’s stories, conduct manuals, a series of state histories, and even an income-tax primer. Interested in publishing a magazine under his name, he launched (after several aborted efforts) the monthly Arthur’s Home Magazine in 1852. Helped by a competent assistant, Virginia Townsend, the magazine survived until several years after Arthur’s death in 1885. The magazine featured Arthur’s tales, other original fare, and articles and stories reprinted from different sources. In 1854, for example, Arthur published Charles Dickens’s Hard Times, apparently with permission.

1854 was also the year Arthur published Ten Nights in a Bar-Room. The story of a small-town miller (perhaps based on Arthur’s father) who gives up his trade to open a tavern; the novel’s narrator is an infrequent visitor who, over several years, traces the physical and moral decline of the proprietor, his family, and the town’s citizenry due to alcohol. The novel sold well but implanted itself in the public consciousness, mainly based on a prevalent stage version that appeared soon after the book. The play remained in continuous production well into the 20th century, when at least two movie versions were made.

Arthur died on March 6, 1885, aged 75, at his home in Philadelphia; his death was attributed to “kidney troubles”. He is buried at The Woodlands.