Ann Veronica, A Modern Love Story

One Wednesday afternoon in late September, Ann Veronica Stanley came down from London in a state of solemn excitement and quite resolved to have things out with her father that very evening. She had trembled on the verge of such a resolution before, but this time quite definitely she made it. A crisis had been reached, and she was almost glad it had been reached. She made up her mind on the train home that it should be a decisive crisis. It is for that reason that this novel begins with her there, and neither earlier nor later, for it is the history of this crisis and its consequences that this novel has to tell.

She had a compartment to herself on the train from London to Morningside Park and she sat with both her feet on the seat in an attitude that would certainly have distressed her mother to see and horrified her grandmother beyond measure; she sat with her knees up to her chin and her hands clasped before them, and she was so lost in thought that she discovered with a start, from a lettered lamp, that she was at Morningside Park, and thought she was moving out of the station, whereas she was only moving in. “Lord!” she said. She jumped up at once, caught up a leather clutch containing notebooks, a fat text-book, and a chocolate-and-yellow-covered pamphlet, and leaped neatly from the carriage, only to discover that the train was slowing down and that she had to traverse the full length of the platform past it again as the result of her precipitation. “Sold again,” she remarked. “Idiot!” She raged inwardly while she walked along with that air of self-contained serenity that is proper to a young lady of nearly two-and-twenty under the eye of the world.

She walked down the station approach, past the neat, obtrusive offices of the coal merchant and the house agent, and so to the wicket-gate by the butcher’s shop that led to the field path to her home. Outside the post office stood a no-hatted, blond young man in gray flannels, who was elaborately affixing a stamp to a letter. At the sight of her, he became rigid and a singularly bright shade of pink. She made herself serenely unaware of his existence, though it may be it was his presence that sent her by the field detour instead of by the direct path up the Avenue.

Read or download Book

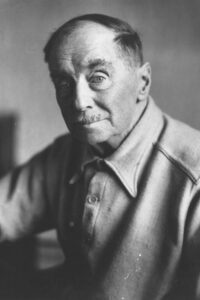

H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer. Prolific in many genres, he wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, history, popular science, satire, biography, and autobiography. Wells’ science fiction novels are so well regarded that he has been called the “father of science fiction”.

In addition to his fame as a writer, he was prominent in his lifetime as a forward-looking, even prophetic social critic who devoted his literary talents to the development of a progressive vision on a global scale. As a futurist, he wrote several utopian works and foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television, and something resembling the World Wide Web. His science fiction imagined time travel, alien invasion, invisibility, and biological engineering before these subjects were common in the genre. Brian Aldiss referred to Wells as the “Shakespeare of science fiction”, while Charles Fort called him a “wild talent”. He also pioneered modern miniature wargaming, such as with his set of rules called Little Wars in 1913.

Wells rendered his works convincing by instilling commonplace detail alongside a single extraordinary assumption per work – dubbed “Wells’s law” – leading Joseph Conrad to hail him in 1898 with “O Realist of the Fantastic!”. His most notable science fiction works include The Time Machine (1895), which was his first novel, The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), the military science fiction The War in the Air (1907), and the dystopian When the Sleeper Wakes (1910). Novels of social realism such as Kipps (1905) and The History of Mr. Polly (1910), which describe lower-middle-class English life, led to the suggestion that he was a worthy successor to Charles Dickens, 99 but Wells described a range of social strata and even attempted, in Tono-Bungay (1909), a diagnosis of English society as a whole. Wells was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times.

Wells’s earliest specialized training was in biology, and his thinking on ethical matters took place in a Darwinian context. He was also an outspoken socialist from a young age, often (but not always, as at the beginning of the First World War) sympathizing with pacifist views. In his later years, he wrote less fiction and more works expounding his political and social views, sometimes giving his profession as that of a journalist. Wells was a diabetic and co-founded the charity The Diabetic Association (Diabetes UK) in 1934.

Life

Early life

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 162 High Street in Bromley, Kent, on 21 September 1866. Called “Bertie” by his family, he was the fourth and last child of Joseph Wells, a former domestic gardener, and at the time a shopkeeper and professional cricketer, and Sarah Neal, a former domestic servant. An inheritance had allowed the family to acquire a shop in which they sold china and sporting goods, although it failed to prosper in part because the stock was old and worn out, and the location was poor. Joseph Wells managed to earn a meager income, but little of it came from the shop and he received an unsteady amount of money from playing professional cricket for the Kent county team.

Writer

Some of his early novels, called “scientific romances”, invented several themes now classic in science fiction in such works as The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds, When the Sleeper Wakes, and The First Men in the Moon. He also wrote realistic novels that received critical acclaim, including Kipps and a critique of English culture during the Edwardian period, Tono-Bungay. Wells also wrote dozens of short stories and novellas, including, “The Flowering of the Strange Orchid”, which helped bring the full impact of Darwin’s revolutionary botanical ideas to a wider public and was followed by many later successes such as “The Country of the Blind” (1904).

According to James E. Gunn, one of Wells’s major contributions to the science fiction genre was his approach, which he referred to as his “new system of ideas”. In his opinion, the author should always strive to make the story as credible as possible, even if both the writer and the reader know certain elements are impossible, allowing the reader to accept the ideas as something that could happen, today referred to as “the plausible impossible” and “suspension of disbelief”. While neither invisibility nor time travel was new in speculative fiction, Wells added a sense of realism to the concepts that the readers were not familiar with. He conceived the idea of using a vehicle that allows an operator to travel purposely and selectively forward or backward in time. The term “time machine”, coined by Wells, is almost universally used to refer to such a vehicle. He explained that while writing The Time Machine, he realized that “the more impossible the story I had to tell, the more ordinary must be the setting, and the circumstances in which I now set the Time Traveller were all that I could imagine of solid upper-class comforts.” In “Wells’s Law”, a science fiction story should contain only a single extraordinary assumption. Therefore, as justification for the impossible, he employed scientific ideas and theories. Wells’s best-known statement of the “law” appears in his introduction to a collection of his works published in 1934:

As soon as the magic trick has been done the whole business of the fantasy writer is to keep everything else human and real. Touches of prosaic detail are imperative and a rigorous adherence to the hypothesis. Any extra fantasy outside the cardinal assumption immediately gives a touch of irresponsible silliness to the invention.

Dr. Griffin / The Invisible Man is a brilliant research scientist who discovers a method of invisibility but finds himself unable to reverse the process. An enthusiast of random and irresponsible violence, Griffin has become an iconic character in horror fiction. The Island of Doctor Moreau sees a shipwrecked man left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, a mad scientist who creates human-like hybrid beings from animals via vivisection. The earliest depiction of uplift, the novel deals with several philosophical themes, including pain and cruelty, moral responsibility, human identity, and human interference with nature. In The First Men in the Moon Wells used the idea of radio communication between astronomical objects, a plot point inspired by Nikola Tesla’s claim that he had received radio signals from Mars. In addition to science fiction, Wells produced work dealing with mythological beings like an angel in The Wonderful Visit (1895) and a mermaid in The Sea Lady (1902).