Germinal

After a time, Étienne also suffered much less from the dampness and closeness of the cutting. The chimney or ascending passage seemed more convenient for climbing up as if he had melted and could pass through cracks where he would not have risked a hand before. He breathed the coal dust without difficulty, saw clearly in the obscurity, and sweated tranquilly, having grown accustomed to the sensation of wet garments on his body from morning to night.

Besides, he no longer wasted his energy; he had gained skill so rapidly that he astonished the whole stall. In three weeks, he was named among the best putters in the pit; no one pushed a tram more quickly to the brow nor loaded it afterwards so correctly. His slight figure allowed him to slip about everywhere, and though his arms were as delicate and white as a woman’s, they seemed to be made of iron beneath the smooth skin, so vigorously did they perform their task.

He never complained out of pride, even when he was panting with fatigue. The only thing they had against him was that he could not take a joke and grew angry as soon as anyone trod on his toes. In all other respects, he was accepted and looked upon as a real miner, reduced beneath this pressure of habit, little by little, to a machine.

Read or download Book

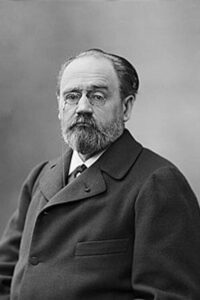

Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (2 April 1840 – 29 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, and playwright. He is the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism and an important contributor to the development of theatrical naturalism.

Biography.

He was a significant figure in the political liberalization of France and in the exoneration of the falsely accused and convicted army officer Alfred Dreyfus, which is encapsulated in his renowned newspaper opinion headlined J’Accuse…! Zola was nominated for the first and second Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901 and 1902.

Early life

Zola was born in Paris in 1840 to François Zola (originally Francesco Zolla) and Émilie Aubert. His father was an Italian engineer with some Greek ancestry who was born in Venice in 1795 and engineered the Zola Dam in Aix-en-Provence; his mother was French. The family moved to Aix-en-Provence in the southeast when Émile was three years old. Four years later, in 1847, his father died, leaving his mother on a meagre pension. In 1858, the Zolas moved to Paris, where Émile’s childhood friend Paul Cézanne soon joined him. Zola started to write in the romantic style. His widowed mother had planned a law career for Émile, but he failed his baccalauréat examination twice.

Later life

In 1862, Zola was naturalized as a French citizen. In 1865, he met Éléonore-Alexandrine Meley, who called herself Gabrielle, a seamstress who became his mistress. They married on 31 May 1870. Together, they cared for Zola’s mother. She stayed with him all his life and actively promoted his work. The marriage remained childless. Alexandrine Zola had a child before she met Zola, and she had given up because she could not take care of it. When she confessed this to Zola after their marriage, they went looking for the girl, but she had died a short time after birth.

In 1888, he was given a camera, but he only began to use it in 1895 and attained a near-professional level of expertise. Also in 1888, Alexandrine hired Jeanne Rozerot, a 21-year-old seamstress, to live with them in their home in Médan. The 48-year-old Zola fell in love with Jeanne and fathered two children with her: Denise in 1889 and Jacques in 1891. After Jeanne left Médan for Paris, Zola continued to support and visit her and their children. In November 1891, Alexandrine discovered the affair, which brought the marriage to the brink of divorce. The discord was partially healed, which allowed Zola to take an increasingly active role in the lives of the children. After Zola’s death, the children were given his name as their lawful surname.

Career

During his early years, Zola wrote numerous short stories, essays, four plays, and three novels. Among his early books was Contes à Ninon, published in 1864. With the publication of his sordid autobiographical novel La Confession de Claude (1865) attracting police attention, Hachette fired Zola. His novel Les Mystères de Marseille appeared as a serial in 1867. He was also an aggressive critic, and his articles on literature and art appeared in Villemessant’s journal L’Événement. After his first major novel, Thérèse Raquin (1867), Zola started the Les Rougon-Macquart series.

In Paris, Zola maintained his friendship with Cézanne, who painted a portrait of him with another friend from Aix-en-Provence, writer Paul Alexis, entitled Paul Alexis Reading to Zola.