Green Mansions, A Romance of the Tropical Forest

I take up pen for this foreword with the fear of one who knows that he cannot do justice to his subject, and the trembling of one who would not, for a good deal, set down words unpleasing to the eye of him who wrote Green Mansions, The Purple Land, and all those other books which have meant so much to me. For of all living authors—now that Tolstoi has gone I could least dispense with W. H. Hudson. Why do I love his writing so much? I think because he is, of living writers that I read, the rarest spirit, and has the clearest gift of conveying to me the nature of that spirit. Writers are to their readers little new worlds to be explored; and each traveler in the realms of literature must needs to have a favorite hunting ground, which, in his goodwill—or perhaps merely in his egoism—he would wish others to share with him.

The great and abiding misfortunes of most of us writers are twofold: We are, as worlds, rather common tramping-ground for our readers, rather tame territory; and as guides and dragomans thereto we are too superficial, lacking clear intimacy of expression; in fact—like guide or dragoman—we cannot let folk into the real secrets, or show them the spirit, of the land.

Now, Hudson, whether in a pure romance like Green Mansions, or in that romantic piece of realism The Purple Land, or books like Idle Days in Patagonia, Afoot in England, The Land’s End, Adventures among Birds, A Shepherd’s Life, and all his other nomadic records of communings with men, birds, beasts, and Nature, has a supreme gift of disclosing not only the thing he sees but the spirit of his vision. Without apparent effort, he takes you with him into a rare, free, natural world, and you are always refreshed, stimulated, and enlarged, by going there.

He is of course a distinguished naturalist, probably the most acute, broad-minded, and understanding observer of Nature living.

And this, in an age of specialism, which loves to put men into pigeonholes and label them, has been a misfortune to the reading public, who seeing the label Naturalist, pass on, and take down the nearest novel. Hudson has indeed the gifts and knowledge of a Naturalist, but that is a mere fraction of his value and interest. A great writer such as this is no more to be circumscribed by a single word than America by the part of it called New York. The expert knowledge which Hudson has of Nature gives to all his work backbone and surety of fiber, and his sense of beauty and intimate actuality. But his real eminence and extraordinary attraction lie in his spirit and philosophy. We feel from his writings that he is nearer to Nature than other men, and yet more truly civilized. The competitive, towny culture, the queer up-to-date commercial knowingness with which we are so busy coating ourselves simply will not stick to him. A passage in his Hampshire Days describes him better than I can: “The blue sky, the brown soil beneath, the grass, the trees, the animals, the wind, and rain, and stars are never strange to me; for I am in and of and am one with them, and my flesh and the soil are one, and the heat in my blood and the sunshine are one, and the winds and the tempests and my passions are one. I feel the ‘strangeness’ only about my fellow men, especially in towns, where they exist in conditions unnatural to me, but congenial to them…. In such moments we sometimes feel a kinship with, and are strangely drawn to, the dead, who were not as these; the long, long dead, the men who knew not life in towns, and felt no strangeness in sun and wind and rain.”

Read or download Book

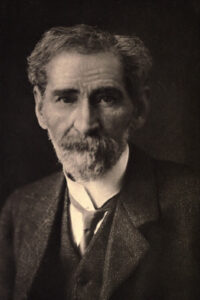

William Henry Hudson

William Henry Hudson (4 August 1841 – 18 August 1922), known in Argentina as Guillermo Enrique Hudson, was an Anglo-Argentine author, naturalist and ornithologist.

Life

Hudson was the son of Daniel Hudson and his wife Catherine (née Kemble), United States settlers of English and Irish origin. He was born and lived his first years in a small estancia called “25 Ombues” in what is now Ingeniero Allan, Florencio Varela, Argentina.

In 1846 the family established a pulpería further south, in the surroundings of Chascomús, not far from the lake of the same name. In this natural environment, Hudson spent his youth studying the local flora and fauna and observing both natural and human dramas on what was then a lawless frontier, while publishing his ornithological work in Proceedings of the Royal Zoological Society initially in an English mingled with Spanish idioms. He had a special love for Patagonia.

Hudson emigrated to England in 1874, taking up residence at St Luke’s Road in Bayswater, where he continued to live for most of his life; in 1876 he married his landlady, the former singer Emily Wingrave, in Kensington, London. One of the daughters of John Hanmer Wingrave, she was some eleven years older than Hudson, having been born on 22 December 1829. He supported himself as a writer and journalist; the couple had no children. Hudson himself was naturalized as a British subject on 4 July 1900.

Hudson was a friend of the late 19th-century English author George Gissing, whom he met in 1889. They corresponded until the latter’s death in 1903, occasionally exchanging their publications, discussing literary and scientific matters, and commenting on their respective access to books and newspapers, a matter of supreme importance to Gissing.

He campaigned (1900) against the building of the National Physical Laboratory on the grounds of Kew Gardens.

In 1911 Emily Hudson became an invalid and moved to Worthing in Sussex. After that, Hudson lived apart from her “for reasons of his health”, although it is clear from their abundant surviving correspondence that he visited her frequently and they remained on affectionate terms.

Hudson died on 18 August 1922, at 40 St Luke’s Road, Westbourne Park, Bayswater, and was buried in Broadwater and Worthing Cemetery, Worthing, on 22 August 1922, next to his wife, who had died early in 1921.

Hudson left an estate valued at £8225, and his Executors were the publisher Ernest Bell and Wynnard Hooper, a journalist.

Books

He produced a series of ornithological studies, including Argentine Ornithology (1888–1899) and British Birds (1895), and later achieved fame with his books on the English countryside, all of them set in Wiltshire, including Hampshire Days (1903), Afoot in England (1909), and A Shepherd’s Life (1910), which helped foster the back-to-nature movement of the 1920s and 1930s.

Hudson’s best-known novel is Green Mansions (1904), which was adapted into a film starring Audrey Hepburn and Anthony Perkins, and his best-known non-fiction is Far Away and Long Ago (1918), which was also made into a film.