Macaria

The flickering light fell upon the pages of a ledger and flashed fitfully in the face of the accountant as he bent over his work. Sixteen years of growth had given him unusual height and remarkable breadth of chest, and it was difficult to realize that a mere boy had attained the stature of manhood in years. A grey suit (evidently home-made), of rather coarse texture, bespoke poverty; and, owing to the oppressive heat of the atmosphere, the coat was thrown partially off. He wore no vest, and the loosely-tied black ribbon suffered the snowy white collar to fall away from the throat and expose its well-turned outline. The head was large, but faultlessly proportioned, and the thick black hair, cut short and clinging to the temples, added to its massiveness. The lofty forehead, white and smooth, the somewhat heavy brows matching the hue of the hair, the straight, finely-formed nose with its delicate but clearly defined nostril, the full firm lips unshaded by a mustache, combined to render the face one of uncommon beauty. Yet, as he sat absorbed by his figures, nothing was prepossessing or winning in his appearance, for though you could not carp at the molding of his features, you involuntarily shrank from the prematurely grave, nay, austere expression that seemed habitual to them. He looked just what he was, youthful in years, but old in trials and labors, and to one who analyzed his countenance, the conviction was inevitable that his will was gigantic, his ambition unbounded, his intellect wonderfully acute and powerful.

“Russell, do you know it is midnight?”

He frowned, and answered without looking up—

“Yes.”

“How much longer will you sit up?”

“Till I finish my work.”

The speaker stood on the threshold, leaning against the door facing, and, after waiting a few moments, softly crossed the room and put her hand on the back of his chair. She was two years his junior, and though the victim of recent and severe illness, even in her feebleness she was singularly like him. Her presence seemed to annoy him, for he turned round and said hastily: “Electra, go to bed. I told you good night three hours ago.”

She stood still, but silent.

Read or download Book

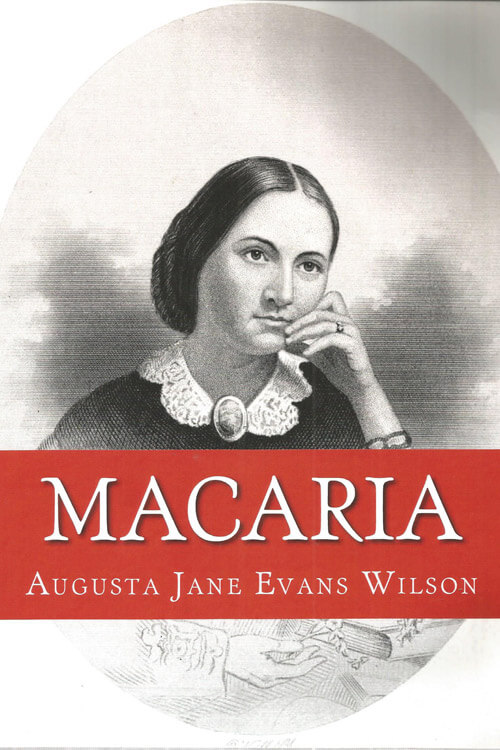

Augusta Jane Evans

Augusta Jane Evans Wilson (May 8, 1835 – May 9, 1909), was an American author of Southern literature and a supporter of the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Her books were banned by the American Library Association in 1881. She was the first woman to earn US$100,000 through her writing.

Wilson was a native of Columbus, Georgia. Her first book, Inez, a Tale of the Alamo, was written when she was still young and published by Harpers. Her second book, Beulah, was issued in 1859 and became at once popular, still selling well when the American Civil War began. Cut off from the world of publishers, and intensely concerned for the cause of secession, she wrote nothing more until several years later when she published her third story, Macaria, dedicated to the soldiers of the Confederate Army. This book was burned by some protesters. After the war closed, Wilson traveled to New York with a copy of St. Elmo, which was published and met with great success. Her later works, Vashti; Infelice; and At the Mercy of Tiberius were also popular. In 1868, she married Lorenzo Madison Wilson, of Alabama, and they resided at Spring Hill.

Early years

Augusta Jane Evans was born on May 8, 1835, in Columbus, Georgia,[6] the eldest child of the family. The area of her birth was then known as Wynnton (now MidTown). Her mother was Sarah S. Howard and her father was Matthew R. Evans. She was a descendant on her mother’s side from the Howards, a prominent Georgia family. She received little formal education but was reportedly a voracious reader at an early age.

Her father suffered bankruptcy and lost the family’s Sherwood Hall property in the 1840s. He moved his family of ten from Georgia to Alabama, and Augusta was ten when they moved to San Antonio, Texas, in 1845. After the Mexican–American War ended, Evans was educated by her mother. During the Mexican war, San Antonio was the rendezvous for the United States troops sent to assist General Zachary Taylor and Evans’s memories of her childhood in San Antonio during the war inspired her first novel. In 1850, at the age of fifteen, she wrote Inez: A Tale of the Alamo, a sentimental, moralistic, and anti-Catholic love story. It told the story of one orphan’s spiritual journey from religious skepticism to devout faith. She presented the manuscript to her father as a Christmas gift in 1854. It was published anonymously in 1855.

By 1849, Evans’ parents moved the family to Mobile, Alabama. She wrote her next novel, Beulah, at age 18; it was published in 1859. Beulah began the theme of female education in her novels. It sold over 22,000 copies during its first year of publication and established her as Alabama’s first professional author. Her family used the proceeds from her literary success to purchase Georgia Cottage on Springhill Avenue.

Career

Civil War

After most of the Southern states declared their independence and seceded from the Union into the Confederate States of America, Evans became a staunch supporter of the Confederacy. Her brothers had joined the 3rd Alabama Regiment and, when she traveled to visit them in Virginia, her party was fired upon by Union soldiers from Fort Monroe. “O! I longed for a Secession flag to shake defiantly in their teeth at every fire! And my fingers fairly itched to touch off a red hot ball in answer to their chivalric civilities”, she wrote to a friend. She became active in the subsequent Civil War as a propagandist. Evans had been engaged to a New York journalist named James Reed Spalding but broke off the engagement in 1860 because Spalding supported Abraham Lincoln. She nursed sick and wounded Confederate soldiers at Fort Morgan on Mobile Bay. Evans also visited Confederate soldiers at Chickamauga. She sewed sandbags for the defense of the community, wrote patriotic addresses, and set up a hospital near her residence. The hospital was dubbed Camp Beulah in honor of her novel. She also corresponded with General P.G.T. de Beauregard in 1862.