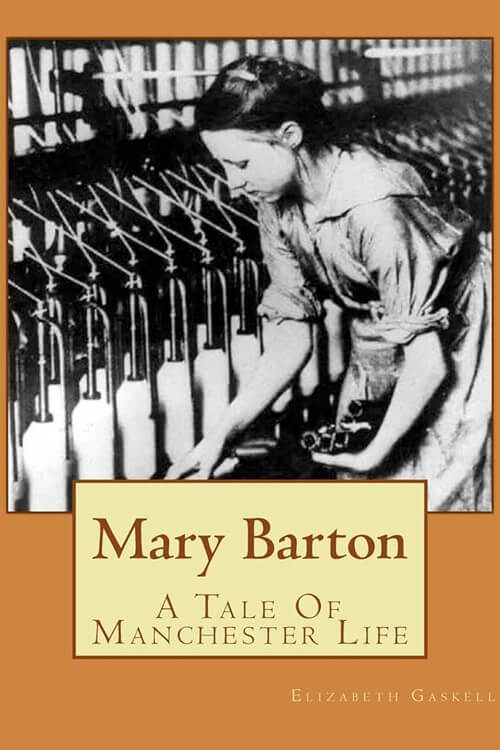

Mary Barton, A Tale of Manchester Life

There are some fields near Manchester, well known to the inhabitants as “Green Heys Fields,” through which runs a public footpath to a little village about two miles distant. Despite these fields being flat and low, nay, despite the want of wood (the great and usual recommendation of level tracts of land), there is a charm about them that strikes even the inhabitant of a mountainous district, who sees and feels the effect of contrast in these common-place but thoroughly rural fields, with the busy, bustling manufacturing town he left but half-an-hour ago. Here and there an old black and white farmhouse, with its rambling outbuildings, speaks of other times and other occupations than those which now absorb the population of the neighborhood.

Here in their seasons may be seen the country business of hay-making, plowing, &c., which are such pleasant mysteries for townspeople to watch; and here the artisan, deafened with the noise of tongues and engines, may come to listen awhile to the delicious sounds of rural life: the lowing of cattle, the milkmaid’s call, the clatter and cackle of poultry in the old farm-yards. You cannot wonder, then, that these fields are popular places of the resort at every holiday time; and you would not wonder if you could see, or I properly describe, the charm of one particular style, that it should be, on such occasions, a crowded halting-place. Close by it is a deep, clear pond, reflecting in its dark green depths the shadowy trees that bend over it to exclude the sun. The only place where its banks are shelving is on the side next to a rambling farmyard, belonging to one of those old-world, gabled, black-and-white houses I named above, overlooking the field through which the public footpath leads.

The porch of this farm-house is covered by a rose tree; and the little garden surrounding it is crowded with a medley of old-fashioned herbs and flowers, planted long ago, when the garden was the only druggist’s shop within reach, and allowed to grow in scrambling and wild luxuriance—roses, lavender, sage, balm (for tea), rosemary, pinks and wallflowers, onions and jessamine, in most republican and indiscriminate order. This farm-house and garden are within a hundred yards of the stile of which I spoke, leading from the large pasture field into a smaller one, divided by a hedge of hawthorn and black-thorn; and near this stile, on the further side, there runs a tale that primroses may often be found, and occasionally the blue sweet violet on the grassy hedge bank.

Read or download Book

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell (29 September 1810 – 12 November 1865), often referred to as Mrs Gaskell, was an English novelist, biographer, and short story writer. Her novels offer a detailed portrait of the lives of many strata of Victorian society, including the very poor. Her first novel, Mary Barton, was published in 1848. Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Brontë, published in 1857, was the first biography of Charlotte Brontë. In this biography, she wrote only of the moral, sophisticated things in Brontë’s life; the rest she omitted, deciding certain, more salacious aspects were better kept hidden. Among Gaskell’s best-known novels are Cranford (1851–1853), North and South (1854–1855), and Wives and Daughters (1864–1866), all of which were adapted for television by the BBC.

Early life

Gaskell was born Elizabeth Cleghorn Stevenson on 29 September 1810 in Lindsey Row, Chelsea, London, now 93 Cheyne Walk. The doctor who delivered her was Anthony Todd Thomson and Thomson’s sister Catherine later became Gaskell’s stepmother. She was the youngest of eight children; only she and her brother John survived infancy. Her father, William Stevenson, a Unitarian from Berwick-upon-Tweed, was minister at Failsworth, Lancashire, but resigned his orders on conscientious grounds. He moved to London in 1806 to go to India after he was appointed private secretary to the Earl of Lauderdale, who was to become Governor General of India. That position did not materialize, however, and Stevenson was nominated Keeper of the Treasury Records.

His wife, Elizabeth Holland, came from a family established in Lancashire and Cheshire that was connected with other prominent Unitarian families, including the Wedgwoods, the Martineaus, the Turners, and the Darwins. When she died 13 months after giving birth to Gaskell, her husband sent Gaskell to live with her mother’s sister, Hannah Lumb, in Knutsford, Cheshire.

Her father remarried Catherine Thomson, in 1814. They had a son, William, in 1815, and a daughter, Catherine, in 1816. Although Elizabeth spent several years without seeing her father, to whom she was devoted, her older brother John often visited her in Knutsford. John was destined for the Royal Navy from an early age, like his grandfathers and uncles, but he did not obtain preferment for the Service and had to join the Merchant Navy with the East India Company’s fleet. John went missing in 1827 during an expedition to India.

Character and influences

A beautiful young woman, Elizabeth was well-groomed, tidily dressed, kind, gentle, and considerate of others. Her temperament was calm and collected, joyous and innocent, she reveled in the simplicity of rural life. Much of Elizabeth’s childhood was spent in Cheshire, where she lived with her aunt Hannah Lumb in Knutsford, the town she immortalized as Cranford. They lived in a large red-brick house called The Heath (now Heathwaite).

From 1821 to 1826 she attended a school in Warwickshire run by the Misses Byerley, first at Barford and from 1824 at Avonbank outside Stratford-on-Avon, where she received the traditional education in arts, the classics, decorum, and propriety given to young ladies from relatively wealthy families at the time. Her aunts gave her the classics to read, and she was encouraged by her father in her studies and writing. Her brother John sent her modern books, and descriptions of his life at sea and his experiences abroad.

After leaving school at the age of 16, Elizabeth traveled to London to spend time with her Holland cousins. She also spent some time in Newcastle upon Tyne (with the Rev William Turner’s family) and from there made the journey to Edinburgh. Her stepmother’s brother was the miniature artist William John Thomson, who in 1832 painted a portrait of Elizabeth Gaskell in Manchester (see top right). A bust was sculpted by David Dunbar at the same time.