Miss Cayley’s Adventures

On the day when I found myself with twopence in my pocket, I naturally made up my mind to go around the world.

It was my stepfather’s death that drove me to it. I had never seen my stepfather. Indeed, I never even thought of him as anything more than Colonel Watts-Morgan. I owed him nothing, except my poverty. He married my dear mother when I was a girl at school in Switzerland; and he proceeded to spend her little fortune, left at her sole disposal by my father’s will, in paying his gambling debts. After that, he carried my dear mother off to Burma; and when he and the climate between them had succeeded in killing her, he made up for his appropriations at the cheapest rate by allowing me just enough to send me to Girton. So, when the Colonel died, in the year I was leaving college, I did not think it necessary to go into mourning for him. Especially as he chose the precise moment when my allowance was due, and bequeathed me nothing but his consolidated liabilities.

‘Of course you will teach,’ said Elsie Petheridge, when I explained my affairs to her. ‘There is a good demand just now for high-school teachers.’

I looked at her, aghast. ‘Teach! Elsie,’ I cried. (I had come up to town to settle her in at her unfurnished lodgings.) ‘Did you say teach? That’s just like you dear good schoolmistresses! You go to Cambridge, and get examined till the heart and life have been examined out of you; then you say to yourselves at the end of it all, “Let me see; what am I good for now? I’m just about fit to go away and examine other people!” That’s what our Principal would call “a vicious circle”—if one could ever admit there was anything vicious at all about you, dear. No, Elsie, I do not propose to teach. Nature did not cut me out for a high-school teacher. I couldn’t swallow a poker if I tried for weeks. Pokers don’t agree with me. Between ourselves, I am a bit of a rebel.’

‘You are, Brownie,’ she answered, pausing in her papering, with her sleeves rolled up—they called me ‘Brownie,’ partly because of my dark complexion, but partly because they could never understand me. ‘We all knew that long ago.’

I laid down the paste brush and mused.

Read or download Book

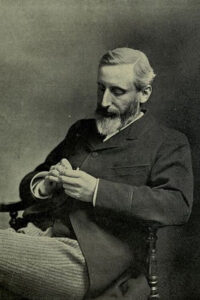

Grant Allen

Charles Grant Blairfindie Allen (February 24, 1848 – October 25, 1899) was a Canadian science writer and novelist, educated in England. He was a public promoter of evolution in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Biography

Allen was born on Wolfe Island near Kingston, Canada West (known as Ontario after Confederation), the second son of Catharine Ann Grant and the Rev. Joseph Antisell Allen, a Protestant minister from Dublin, Ireland. His mother was a daughter of the fifth Baron de Longueuil. Allen was educated at home until, at age 13, he and his parents moved to the United States, then to France, and finally to the United Kingdom. He was educated at King Edward’s School in Birmingham and Merton College in Oxford, both in the United Kingdom.

After graduation, Allen studied in France, taught at Brighton College in 1870–71, and his mid-twenties became a professor at Queen’s College, a black college in Jamaica. Despite being the son of a minister, Allen became an atheist and a socialist.

Writing career

After leaving his professorship, in 1876 he returned to England, where he turned his talents to writing, gaining a reputation for his science essays and literary works. A 2007 book by Oliver Sacks cites with approval one of Allen’s early articles, “Note-Deafness” (a description of what became known as amusia, published in 1878 in the learned journal Mind).

Allen’s first books dealt with scientific subjects, including Physiological Æsthetics (1877) and Flowers and Their Pedigrees (1886) He was first influenced by associationist psychology as expounded by Alexander Bain and by Herbert Spencer, the latter who especially espoused the transition from associationist psychology to Darwinian functionalism. In Allen’s many articles on flowers and perception in insects, Darwinian arguments replaced the old Spencerian terms, leading to a radically new vision of plant life that influenced H.G. Wells and helped transform later botanical research.

On a personal level, a long friendship that started when Allen met Spencer on his return from Jamaica grew uneasy over the years. Allen wrote a critical and revealing biographical article on Spencer that was published after Spencer’s death.

After assisting Sir W. W. Hunter with his Gazetteer of India in the early 1880s, Allen turned his attention to fiction, and between 1884 and 1899 produced about 30 novels. In 1895, his scandalous book titled The Woman Who Did, promulgating certain startling views on marriage and kindred questions became a bestseller. The book tells the story of an independent woman who has a child out of wedlock. Owing to his concern with these subjects, Allen was associated with Thomas Hardy, whose novel Jude the Obscure (1895) was published the same year as The Woman Who Did.

In his career, Allen wrote two novels under female pseudonyms. One of these is the short novel The Type-writer Girl, which he wrote under the name Olive Pratt Rayner.

Another work, The Evolution of the Idea of God (1897), propounds a theory of religion on heterodox lines comparable to Herbert Spencer’s “ghost theory”. Allen’s theory became well known and brief references to it appear in a review by Marcel Mauss, Durkheim’s nephew, in the articles of William James and the works of Sigmund Freud. G. K. Chesterton wrote on what he considered the flawed premise of the idea, arguing that the idea of God preceded human mythologies, rather than developing from them. Chesterton said of Allen’s book on the evolution of the idea of God: “It would be much more interesting if God wrote a book on the evolution of the idea of Grant Allen”.

Allen also became a pioneer in science fiction, with the novel The British Barbarians (1895) This book, published about the same time as H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine (which appeared in January–May 1895, and which includes a mention of Allen), also described time travel, although the plot is quite different. Allen’s short story The Thames Valley Catastrophe (published December 1897 in The Strand Magazine) describes the destruction of London by a sudden and massive volcanic eruption.