Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon, finding his proffers of peace rejected by England with contumely and scorn and declined by Austria, now prepared, with his customary energy, to repel the assaults of the allies. As he sat in his cabinet at the Tuileries, the thunders of their unrelenting onset came rolling in upon his ear from all the frontiers of France. The hostile fleets of England swept the channel, utterly annihilating the commerce of the Republic, landing regiments of armed emigrants upon her coast, furnishing money and munitions of war to rouse the partisans of the Bourbons to civil conflict, and throwing balls and shells into every unprotected town. On the northern frontier, Marshal Kray came thundering down, through the Black Forest, to the banks of the Rhine, with a mighty host of 150,000 men, like locust legions, to pour into all the northern provinces of France. Artillery of the heaviest caliber and a magnificent array of cavalry accompanied this invincible army. In Italy, Melas, another Austrian marshal, with 140,000 men, aided by the whole force of the British navy, was rushing upon the eastern and southern borders of the Republic. The French troops, disheartened by defeat, had fled before their foes over the Alps or were eating their horses and their boots in the cities where they were besieged. From almost every promontory on the coast of the Republic, washed by the Channel, or the Mediterranean, the eye could discern English frigates, black and threatening, holding all France in a state of blockade.

One always finds a certain pleasure in doing that which he can do well. Napoleon was fully conscious of his military genius. He had, on behalf of bleeding humanity, implored peace in vain. He now, with alacrity and with joy, roused himself to inflict blows that should be felt upon his multitudinous enemies. With such tremendous energy did he do this, that he received from his antagonists the most complimentary sobriquet of the one hundred thousand men.

Wherever Napoleon made his appearance in the field, his presence alone was considered equivalent to that force.

The following proclamation rang like a trumpet charge over the hills and valleys of France. “Frenchmen! You have been anxious for peace. Your government has desired it with still greater ardor.

Its first efforts, its most constant wishes, have been for its attainment. The English ministry has exposed the secret of its iniquitous policy. It wishes to dismember France, to destroy its commerce, and either to erase it from the map of Europe or to degrade it to a secondary power. England is willing to embroil all the nations of the Continent in hostility with each other, that she may enrich herself with their spoils, and gain possession of the trade of the world. For the attainment of this object, she scatters her gold, becomes prodigal of her promises, and multiplies her intrigues.”

At this call, all the martial spirit of France rushed to arms.

Napoleon, supremely devoted to the welfare of the State, seemed to forget even his glory in the intensity of his desire to make France victorious over her foes. With the most magnanimous superiority to all feelings of jealousy, he raised an army of 150,000 men, the very elite of the troops of France, the veterans of a hundred battles, and placed them in the hands of Moreau, the only man in France who could be called his rival. Napoleon also presented to Moreau the plan of a campaign under his energy, boldness, and genius. Its accomplishment would have added surpassing brilliance to the reputation of Moreau. But the cautious general was afraid to adopt it, and presented another, perhaps as safe, but one which would produce no dazzling impression upon the imaginations of men. “Your plan,” said one, a friend of Moreau, to the First Consul, “is grander, more decisive, even more sure.

Read or download Book

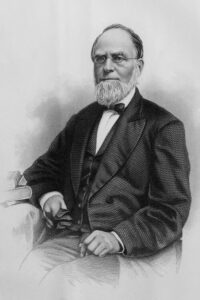

John S. C. Abbott

John Stevens Cabot Abbott (September 19, 1805 – June 17, 1877), an American historian, pastor, and pedagogical writer, was born in Brunswick, Maine to Jacob and Betsey Abbott.

Early life

He was a brother of Jacob Abbott and was associated with him in the management of Abbott’s Institute in New York City, and the preparation of his series of brief historical biographies. Abbott graduated from Bowdoin College in 1825, prepared for the ministry at Andover Theological Seminary, and between 1830 and 1844, when he retired from the ministry in the Congregational Church, preached successively at Worcester, Roxbury, and Nantucket, all in Massachusetts.

Literary career

Owing to the success of his work, The Mother at Home, he devoted himself from 1844 onwards, to literature. He was a voluminous writer of books on Christian ethics, and of popular histories, which were credited with cultivating a popular interest in history. He is best known as the author of the widely popular History of Napoleon Bonaparte (1855), in which the various elements and episodes in Napoleon’s career are described. Abbott takes a very favorable view of his subject throughout. Also among his principal works are: History of the Civil War in America (1863–1866), History of Napoleon III Emperor of the French (1868), and The History of Frederick II, Called Frederick the Great (New York, 1871). He also did a foreword to a book called Life of Boone by W.M. Bogart, about Daniel Boone in 1876.

His biography in The Biographical Dictionary of America (1906) states that Abbot’s mind was extremely clear and active, and he could leave the subject in hand for something entirely different, and then resume his former work without the slightest inconvenience, also he had a singularly even temperament; by his goodness, as well as by his books, he had a great influence on the world, he continued active in work nearly to the time of his death, to which he looked forward with joy rather than resignation. The anonymous author of his biography in the Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.) stated “He was a voluminous writer of books on Christian ethics, and of histories, which now seem unscholarly and untrustworthy, but were valuable in their time in cultivating a popular interest in history”; and that in general, except that he did not write juvenile fiction, his work in subject and style closely resembles that of his brother, Jacob Abbott.