Peck’s Bad Boy with the Cowboys

The first day after the show left us at St. Louis we felt pretty bum, ‘cause we missed the smell of the canvas, and the sawdust, and the animals, and the indescribable odor that goes with a circus. We missed the performers, the band, the surging crowds around the ticket wagon, and the cheers from the seats. It almost seemed as though there had been a funeral in the family, and we were sitting around in the cold parlor waiting for the lawyers to read the will. But in a couple of days Pa got busy, and he hired a young Indian who was a graduate of Carlisle, as an interpreter, and a reformed cowboy, to go with us to the cattle ranges, and an old big game hunter who was to accompany us to the places where we could find buffalo and grizzly bears. Pa chartered a car to take us west, and after the Indian and the cowboy and the hunter got sobered up, on the train, and got the St. Louis ptomaine poison out of their systems, and we were going through Kansas, Pa got us all into the smoking compartment.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “I want you to know that this expedition is backed by the wealth of the circus world and that there is nothing cheap about it. We are to hire, regardless of expense, the best riders, the best cattle ropers, and the best everything that goes with a Wild West show. We all know that Buffalo Bill must soon, like things, pass away as a feature for shows, and I have been selected to take the place of Bill in the circus world when he cashes in. You may have noticed that I have been letting my hair mustache and chin whiskers grow the last few months so that next year I will be a dead ringer for Bill. All I want is some experience as a hero of the plains, as a scout, a hunter, a scalper of Indians, a rider of wild horses, and a few things like that, and next year you will see me ride a white horse up in front of the press seats in our show, take off my broad-brimmed hat, and wave it at the crowned heads in the boxes, give the spurs to my horse, and ride away like a cavalier, and the show will go on, to the music of hand-clapping from the assembled thousands, see?”

The cowboy looked at Pa’s stomach, and said: “Well, Mr. Man, if you are going to blow yourself for a second Buffalo Bill, I am with you, at the salary agreed upon, till the cows come home, but you have got to show me that you have got no yellow streak, when it comes to cutting out steers that are wild and carry long horns, and you’ve got to rope ‘em, and tie ‘em all alone, and hold up your hands for judgment, in ten seconds.”

Read or download Book

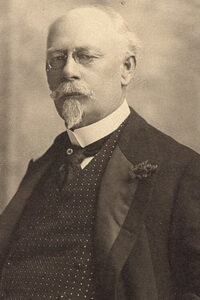

George W. Peck

George Wilbur Peck (September 28, 1840 – April 16, 1916) was an American writer and politician from Wisconsin. He served as the 17th governor of Wisconsin and the 9th mayor of Milwaukee.

Biography.

Peck was born in 1840 in Henderson, New York, the oldest of three children of David B. and Alzina P. (Joslin) Peck. In 1843, the family moved to what is now Cold Spring, Wisconsin. Peck attended public school until age 15 when he was apprenticed in the printing trade. He married Francena Rowley in 1860 and they had two sons. In 1863 he enlisted in the 4th Wisconsin Cavalry Regiment as a private. He was taken prisoner and held at Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. After he was released in a prisoner exchange, he was appointed to the United States Military Academy by Abraham Lincoln. He was promoted to lieutenant and served until the regiment mustered out in 1866.

Peck became a newspaper publisher who founded newspapers in Ripon and La Crosse, Wisconsin. His La Crosse newspaper, The Sun, was founded in 1874. In 1878 Peck moved the newspaper to Milwaukee, renaming it Peck’s Sun. The weekly newspaper contained Peck’s humorous writings, including his famous “Peck’s Bad Boy” stories.

In the spring of 1890, Peck ran for mayor of Milwaukee. A Democrat, Peck was elected despite a Republican majority in the city. The state’s Democratic leaders took notice and made Peck the party’s nominee for the 1890 gubernatorial race. Peck won the election, beating the incumbent William Hoard, and resigned as Milwaukee’s mayor on November 11, 1890. He was reelected as governor in 1892, defeating Republican John C. Spooner, but lost a third term to William Upham in 1894. He ran again in 1904 but lost to the incumbent Robert M. La Follette Sr.

Peck died in 1916 in Milwaukee at age 75 of Bright’s disease and was buried at Forest Home Cemetery. After his death, his “Peck’s Bad Boy” writings became the basis for several films and a short-lived television show, including Peck’s Bad Boy and Peck’s Bad Girl.

His former home in La Crosse is located in what is now known as the 10th and Cass Streets Neighborhood Historic District.