The Belief in Immortality and the Worship of the Dead

Sweet friendship, the happiness of life! parents and friends come to hug us, and offer us their services and their devotion: we entrust them with our darling son, whose young age prevents us from taking with us to visit the native country of beauty, the ravishing Italy. Several times in our rapid journey, we congratulated ourselves for having left our child in such tender care.

The different climates that we were going to travel through could have harvested, at the dawn of its days, this young flower, the life of all our thoughts, and thus covered our existence with mourning and pain. But letters should, on special days, like faithful meetings, bring us balm and give us tranquility in our journey.

Here we are in the coach coupe, preferring this route a thousand times over private cars, and this is to better travel the rivers, lakes, or seas on distant journeys whose various accidents cannot be specified in advance. We had little baggage, to take, so to speak, like Bias, everything with us.

On the road, we see with pleasure the rapid progress of agriculture; the crop rotations shine everywhere in place of the barren follows: since the property is divided up, the less considerable fields are amended and taken care of; so true is it that the subdivision of land is advantageous to the masses and production. I know well that the big owner who asserts himself must act differently. In these wise economic measures, he aims rather at artificial and natural meadows, at the fertilizer of cattle, than at the expensive cultivation of cereals; but it is not so with small farmers. The cultivation of rapeseed, so valuable in a large part of France, is spreading widely in the western departments: The land no longer remains unproductive under our hardworking inhabitants.

Here is the first relay, it is the small town of Montaigu. Here I will not speak of these bloody struggles of principle rather than of people, of the old and the new regime, of freedom or feudalism; the hour of reconciliation has arrived; everyone owns an acre of land and is attached to the soil: freedom of the press has come to soften the warlike mood of these countries: I believe political reactions are impossible, in this beautiful country, covered in funeral crepe, in rubble, and where the blood of so many victims have gushed only too often.

We see soldiers further away, changing winter quarters; humming a few bacchic songs without tripping or having a drunken leg. These frequent migrations are for a political purpose to break the intimate relationships between warriors and townspeople: these soldiers, painfully tired from walking on a muddy road, by the weight of their weapons and their baggage; these descendants of their illustrious predecessors, who carried the glory of the French name even below the icy zone, approach our clarifier to inquire if they could occupy the vacant places; their few coins are not enough for the driver; they are obliged to continue the journey on foot, like the tireless Spartans, consumed with hunger and love for their homeland. Iron roads will one day make it easier for the development of philanthropy, and the military will find a place on hospital wagons.

Read or download Book

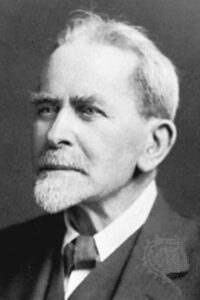

Sir James George Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Personal life

He was born on 1 January 1854 in Glasgow, Scotland, the son of Katherine Brown and Daniel F. Frazer, a chemist.

Frazer attended school at Springfield Academy and Larchfield Academy in Helensburgh. He studied at the University of Glasgow and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he graduated with honors in classics (his dissertation was published years later as The Growth of Plato’s Ideal Theory) and remained a Classics Fellow all his life. From Trinity, he went on to study law at the Middle Temple, but never practiced.

Four times elected to Trinity’s Title Alpha Fellowship, he was associated with the college for most of his life, except for the year 1907–1908, spent at the University of Liverpool. He was knighted in 1914, and a public lectureship in social anthropology at the universities of Cambridge, Oxford, Glasgow, and Liverpool was established in his honor in 1921. He was, if not blind, then severely visually impaired from 1930 on. He and his wife, Lilly, died in Cambridge, England, within a few hours of each other. He died on 7 May 1941. They are buried at the St Giles aka Ascension Parish Burial Ground in Cambridge.

His sister Isabella Katherine Frazer married the mathematician John Steggall.

Frazer is commonly interpreted as an atheist in light of his criticism of Christianity and especially Roman Catholicism in The Golden Bough. However, his later writings and unpublished materials suggest an ambivalent relationship with Neoplatonism and Hermeticism.

In 1896 Frazer married Elizabeth “Lilly” Grove, a writer whose father was from Alsace. She would later adapt Frazer’s Golden Bough as a book of children’s stories, The Leaves from the Golden Bough.

Work

The study of myth and religion became his area of expertise. Except for visits to Italy and Greece, Frazer was not widely traveled. His prime sources of data were ancient histories and questionnaires mailed to missionaries and imperial officials all over the globe. Frazer’s interest in social anthropology was aroused by reading E. B. Tylor’s Primitive Culture (1871) and was also encouraged by his friend, the biblical scholar William Robertson Smith, who was comparing elements of the Old Testament with early Hebrew folklore.

Frazer was the first scholar to describe in detail the relations between myths and rituals. His vision of the annual sacrifice of the Year-King has not been borne out by field studies. Yet The Golden Bough, his study of ancient cults, rites, and myths, including their parallels in early Christianity, continued for many decades to be studied by modern mythographers for its detailed information.

The first edition, in two volumes, was published in 1890; and a second, in three volumes, in 1900. The third edition was finished in 1915 and ran to twelve volumes, with a supplemental thirteenth volume added in 1936. He published a single-volume abridged version, largely compiled by his wife Lady Frazer, in 1922, with some controversial material on Christianity excluded from the text. The work’s influence extended well beyond the conventional bounds of academia, inspiring the new work of psychologists and psychiatrists. Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, cited Totemism and Exogamy frequently in his own Totem and Taboo: Resemblances Between the Psychic Lives of Savages and Neurotics.

The symbolic cycle of life, death, and rebirth which Frazer divined behind myths of many peoples captivated a generation of artists and poets. Perhaps the most notable product of this fascination is T. S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land (1922).

Frazer’s pioneering work has been criticized by late-20th-century scholars. For instance, in the 1980s the social anthropologist Edmund Leach wrote a series of critical articles, one of which was featured as the lead in Anthropology Today, vol. 1 (1985). Leach criticized The Golden Bough for the breadth of comparisons drawn from widely separated cultures but often based his comments on the abridged edition, which omits the supportive archaeological details. In a positive review of a book narrowly focused on the cultus in the Hittite city of Nerik, J. D. Hawkins remarked approvingly in 1973, “The whole work is very methodical and sticks closely to the fully quoted documentary evidence in a way that would have been unfamiliar to the late Sir James Frazer.” More recently, The Golden Bough has been criticized for what is widely perceived as imperialist, anti-Catholic, classist, and racist elements, including Frazer’s assumptions that European peasants, Aboriginal Australians, and Africans represented fossilized, earlier stages of cultural evolution.

Another important work by Frazer is his six-volume commentary on the Greek traveler Pausanias’ description of Greece in the mid-2nd century AD. Since his time, archaeological excavations have added enormously to the knowledge of ancient Greece, but scholars still find much value in his detailed historical and topographical discussions of different sites, and his eyewitness accounts of Greece at the end of the 19th century.