The Wisdom of Father Brown

The consulting rooms of Dr Orion Hood, the eminent criminologist and specialist in certain moral disorders, lay along the sea-front at Scarborough, in a series of very large and well-lighted French windows, which showed the North Sea like one endless outer wall of blue-green marble. In such a place the sea had something of the monotony of a blue-green dado: for the chambers themselves were ruled throughout by a terrible tidiness not unlike the terrible tidiness of the sea. It must not be supposed that Dr Hood’s apartments excluded luxury or even poetry. These things were there, in their place; but one felt that they were never allowed out of their place. Luxury was there: there stood upon a special table eight or ten boxes of the best cigars, but they were built upon a plan so that the strongest were always nearest the wall and the mildest nearest the window. A tantalus containing three kinds of spirit, all of a liqueur excellence, stood always on this table of luxury; but the fanciful have asserted that the whisky, brandy, and rum seemed always to stand at the same level. Poetry was there: the left-hand corner of the room was lined with as complete a set of English classics as the right hand could show of English and foreign physiologists. But if one took a volume of Chaucer or Shelley from that rank, its absence irritated the mind like a gap in a man’s front teeth. One could not say the books were never read; probably they were, but there was a sense of their being chained to their places, like the Bibles in the old churches. Dr. Hood treated his private bookshelf as if it were a public library. And if this strict scientific intangibility steeped even the shelves laden with lyrics and ballads and the tables laden with drink and tobacco, it goes without saying that yet more of such heathen holiness protected the other shelves that held the specialist’s library, and the other tables that sustained the frail and even fairylike instruments of chemistry or mechanics.

Dr Hood paced the length of his string of apartments, bounded— as the boys’ geographies say—on the east by the North Sea and on the west by the serried ranks of his sociological and criminologist library. He was clad in an artist’s velvet, but with none of an artist’s negligence; his hair was heavily shot with grey, but growing thick and healthy; his face was lean, but sanguine and expectant. Everything about him and his room indicated something at once rigid and restless, like that great northern sea by which (on pure principles of hygiene) he had built his home.

Fate, being in a funny mood, pushed the door open and introduced into those long, strict, sea-flanked apartments one who was perhaps the most startling opposite of them and their master. In answer to a curt but civil summons, the door opened inwards and there shambled into the room a shapeless little figure, which seemed to find its hat and umbrella as unmanageable as a mass of luggage. The umbrella was a black and prosaic bundle long past repair; the hat was a broad-curved black hat, clerical but not common in England; the man was the very embodiment of all that is homely and helpless.

Read or download Book

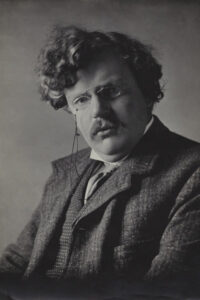

G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton KC*SG (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic.

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brown and wrote on apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognized the wide appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an orthodox Christian and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting from high church Anglicanism. Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, John Henry Newman, and John Ruskin.

He has been referred to as the “prince of paradox”. Of his writing style, Time observed: “Whenever possible, Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out.” His writings were an influence on Jorge Luis Borges, who compared his literature with that of Edgar Allan Poe.

Biography

Early life

Chesterton was born in Campden Hill in Kensington, London, the son of Edward Chesterton (1841–1922), an estate agent, and Marie Louise, née Grosjean, of Swiss-French origin. Chesterton was baptized at the age of one month into the Church of England, though his family was irregularly practicing Unitarians. According to his autobiography, as a young man, he became fascinated with the occult and, along with his brother Cecil, experimented with Ouija boards. He was educated at St Paul’s School, then attended the Slade School of Art to become an illustrator. The Slade is a department of University College London, where Chesterton also took classes in literature, but he did not complete a degree in either subject. He married Frances Blogg in 1901; the marriage lasted the rest of his life. Chesterton credited Frances with leading him back to Anglicanism, though he later considered Anglicanism to be a “pale imitation”. He entered full communion with the Catholic Church in 1922. The couple were unable to have children.

A friend from schooldays was Edmund Clerihew Bentley, inventor of the clerihew, a whimsical four-line biographical poem. Chesterton himself wrote clerihews and illustrated his friend’s first published collection of poetry, Biography for Beginners (1905), which popularised the clerihew form. He became godfather to Bentley’s son, Nicolas, and opened his novel The Man Who Was Thursday with a poem written to Bentley.

Career

In September 1895, Chesterton began working for the London publisher George Redway, where he remained for just over a year. In October 1896, he moved to the publishing house T. Fisher Unwin, where he remained until 1902. During this period he also undertook his first journalistic work, as a freelance art and literary critic. In 1902, The Daily News gave him a weekly opinion column, followed in 1905 by a weekly column in The Illustrated London News, for which he continued to write for the next thirty years.

Early on Chesterton showed a great interest in and talent for art. He had planned to become an artist, and his writing shows a vision that clothed abstract ideas in concrete and memorable images. Father Brown is perpetually correcting the incorrect vision of the bewildered folks at the scene of the crime and wandering off at the end with the criminal to exercise his priestly role of recognition, repentance, and reconciliation. For example, in the story “The Flying Stars”, Father Brown entreats the character Flambeau to give up his life of crime: “There is still youth and honor and humor in you; don’t fancy they will last in that trade. Men may keep a sort of level of good, but no man has ever been able to keep on one level of evil. That road goes down and down. The kind man drinks and turns cruel; the frank man kills and lies about it. Many a man I’ve known started like you to be an honest outlaw, a merry robber of the rich, and ended stamped into slime.”