The Birds

The Birds is not perhaps the funniest of Aristophanes’ plays, but it is generally the most delightful. It is not the fire of the Knights or the Wasps nor the curiously modern issues of thought that startle us in the Clouds and the Frogs. For once the stormy dramatist has allowed himself a play of escape, escape using imagination into a care-free world, far away from the great war-wearied city, with its taxes and regulations and prohibitions and fines and the follies of its exasperated demos; away from mankind, creatures “so dimly alive,” shadows and pursuers of shadows, toiling so much and accomplishing so little; away perhaps even from the gods who now claim to rule the world, and are making such a very poor business of it. There is a tradition, he might remember, that our ancestors had other gods before these anthropomorphic Olympians were introduced; sometimes, it may be, they worshipped birds; how much more sensible! The Birds ask for so little and have so much to give. They want no great temples or sacrifices; they insist on no long pilgrimages before they will speak to us. They are here, living, flying, and singing among us; we can see the joy that is in their hearts, the joy that we creatures of clay can never reach. Yet if we worshipped them rightly, who knows? they might let us have some share in it.

Aristophanes must have known his birds very well he names an extraordinary number of species, some of which even Professor Darcy Thompson has not been able to identify. Of course, he makes them all ridiculous, except perhaps the Nightingale; he laughs at them and loves them, and he seems to have, almost alone in antiquity, a Blake-like hatred of seeing a bird caged or tethered.

Life in Athens must have been difficult in 414 b.c., when this play was produced, a year of wild hope and anxiety and suspicion. The previous year had seen the unprovoked siege and massacre of Melos, which seems to have been selected by Thucydides for detailed analysis as forming the climax of the ever-growing violence characteristic of the dominant ultra-democratic war party and must have cast a gloom on the more conscientious minority who were now powerless. It was immediately followed by an expedition, with the greatest naval force ever seen, to establish the Athenian rule over Syracuse and all Sicily and perhaps more. Was this a splendid military enterprise, or was it, as the old poets would have said, a manifest case of Hubris begetting Atê and leading to certain death? Opinion was divided; the brilliant and ambitious Alcibiades was for the adventure, the experienced and hitherto successful Nikias against it. Just before the fleet sailed, however, there occurred a curious outrage which shows how closely enlightened Athens was still haunted by primitive superstitious fears. The stone pillars with human heads and symbols of fertility, called “Hermae,” which stood as landmarks throughout the city, were, all but one, mutilated in a single night. Later inquiries led to the conclusion that it was only a drunken frolic by members of a smart and “enlightened” oligarchic club, but to the mass of the people such a mutilation was an omen of the worst possible significance. Coming to an overstrained populace on the very eve of their greatest and most dangerous enterprise, it produced a storm of hysterical alarm and suspicion. There were rumors of malignant treason; rumors of profanations of the mysteries. Informers, oracle-mongers, political charlatans, all the classes whom Aristophanes most detested, set to work to stir up trouble and persecution. And, though no disaster to the Sicilian armada had yet occurred, to men like Aristophanes the atmosphere must have been such as to intensify the worry and discontent produced by the long war and the concentration of power in the hands of men whom they despised. He did not protest as he had in the Knights, Acharnians, and Wasps. Perhaps it was too dangerous after the law passed in 415 forbidding personal attacks in comedy. Perhaps he was merely anxious not to increase the existing trouble and discord. He took refuge in poetry. He makes passing allusions to a great many artists and public men in the course of the play, so many that I have thought it helpful to make an alphabetical list of them. He lashes a few of his old bêtes noires like the fat warmonger Cleônymus, but on the whole, he keeps clear of politics, and entirely clear of the most dangerous issues. There is no mention of the Hermae or the Sicilian expedition. No doubt he had his prejudices, but it is worth noting that nearly all the individuals whom he pillories in The Birds are condemned by subsequent history.

Read or download Book

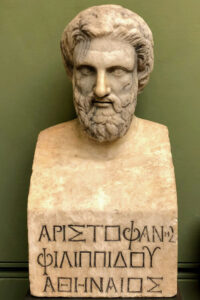

Aristophanes

Aristophanes ( c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus and Zenodora, of the deme Kydathenaion (Latin: Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy.

Biography.

Eleven of his forty plays survive virtually complete. These provide the most valuable examples of a genre of comic drama known as Old Comedy and are used to define it, along with fragments from dozens of lost plays by Aristophanes and his contemporaries.

Also known as “The Father of Comedy” and “the Prince of Ancient Comedy”, Aristophanes has been said to recreate the life of ancient Athens more convincingly than any other author. His powers of ridicule were feared and acknowledged by influential contemporaries; Plato singled out Aristophanes’ play The Clouds as slander that contributed to the trial and subsequent condemning of the death of Socrates, although other satirical playwrights had also caricatured the philosopher.

Aristophanes’ second play, The Babylonians (now lost), was denounced by Cleon as a slander against the Athenian polis. It is possible that the case was argued in court, but details of the trial are not recorded and Aristophanes caricatured Cleon mercilessly in his subsequent plays, especially The Knights, the first of many plays that he directed himself. “In my opinion,” he says through that play’s Chorus, “the author-director of comedies has the hardest job of all.”

Aristophanes’s name means ‘one who appears best’, from the Greek ‘ἄριστος’ (Aristos) meaning “best” and ‘φαίνομαι’, meaning “appear”.

Less is known about Aristophanes than about his plays. His plays are the main source of information about him and his life. It was conventional in Old Comedy for the chorus to speak on behalf of the author during an address called the parabasis and thus some biographical facts can be found there. However, these facts relate almost entirely to his career as a dramatist and the plays contain few unambiguous clues about his personal beliefs or his private life. He was a comic poet in an age when it was conventional for a poet to assume the role of teacher (didaskalos), and though this specifically referred to his training of the Chorus in rehearsal, it also covered his relationship with the audience as a commentator on significant issues.

Aristophanes claimed to be writing for a clever and discerning audience, yet he also declared that “other times” would judge the audience according to the reception of his plays. He sometimes boasts of his originality as a dramatist yet his plays consistently espouse opposition to radical new influences in Athenian society. He caricatured leading figures in the arts (notably Euripides, whose influence on his work however he once grudgingly acknowledged), in politics (especially the populist Cleon), and in philosophy/religion (where Socrates was the most obvious target). Such caricatures seem to imply that Aristophanes was an old-fashioned conservative, yet that view of him leads to contradictions.

It has been argued that Aristophanes produced plays mainly to entertain the audience and to win prestigious competitions. His plays were written for production at the great dramatic festivals of Athens, the Lenaia, and City Dionysia, where they were judged and awarded prizes in competition with the works of other comic dramatists. An elaborate series of lotteries, designed to prevent prejudice and corruption, reduced the voting judges at the City Dionysia to just five. These judges probably reflected the mood of the audiences yet there is much uncertainty about the composition of those audiences. The theatres were certainly huge, with seating for at least 10,000 at the Theatre of Dionysus. The day’s program at the City Dionysia for example was crowded, with three tragedies and a satyr play ahead of a comedy, but it is possible that many of the poorer citizens (typically the main supporters of demagogues like Cleon) occupied the festival holiday with other pursuits. The conservative views expressed in the plays might therefore reflect the attitudes of the dominant group in an unrepresentative audience.