The Chessmen of Mars

Shea had just beaten me at chess, as usual, and, also as usual, I had gleaned what questionable satisfaction I might by twitting him with this indication of failing mentality by calling his attention for the nth time to that theory, propounded by certain scientists, which is based upon the assertion that phenomenal chess players are always found to be from the ranks of children under twelve, adults over seventy-two or the mentally defective—a theory that is lightly ignored upon those rare occasions that I win. Shea had gone to bed and I should have followed suit, for we are always in the saddle here before sunrise; but instead, I sat there before the chess table in the library, idly blowing smoke at the dishonored head of my defeated king.

While thus profitably employed I heard the east door of the living room open and someone enter. I thought it was Shea returning to speak with me on some matter of tomorrow’s work; but when I raised my eyes to the doorway that connects the two rooms I saw framed there the figure of a bronzed giant, his otherwise naked body trapped with a jewel-encrusted harness from which there hung at one side an ornate short-sword and at the other a pistol of strange pattern. The black hair, the steel-gray eyes, brave and smiling, the noble features—I recognized them at once, and leaping to my feet I advanced with an outstretched hand.

“John Carter!” I cried. “You?”

“None other, my son,” he replied, taking my hand in one of his and placing the other upon my shoulder.

“And what are you doing here?” I asked. “It has been long years since you revisited Earth, and never before in the trappings of Mars. Lord! but it is good to see you—and not a day older in appearance than when you trotted me on your knee in my babyhood. How do you explain it, John Carter, Warlord of Mars, or do you try to explain it?”

“Why attempt to explain the inexplicable?” he replied. “As I have told you before, I am a very old man. I do not know how old I am. I recall no childhood, but recollect only having been always as you see me now and as you saw me first when you were five years old. You, yourself, have aged, though not as much as most men in a corresponding number of years, which may be accounted for by the fact that the same blood runs in our veins; but I have not aged at all. I have discussed the question with a noted Martian scientist, a friend of mine; but his theories are still only theories. However, I am content with the fact—I never age, and I love life and the vigor of youth.

“And now as to your natural question as to what brings me to Earth again and in this, to earthly eyes, strange habiliment. We may thank Kar Komak, the bowman of Lothar. It was he who gave me the idea upon which I have been experimenting until at last I have achieved success. As you know I have long possessed the power to cross the void in spirit, but never before have I been able to impart to inanimate things a similar power. Now, however, you see me for the first time precisely as my Martian fellows see me—you see the very short sword that has tasted the blood of many a savage foeman; the harness with the devices of Helium and the insignia of my rank; the pistol that was presented to me by Tars Tarkas, Jeddak of Thark.

Read or download Book

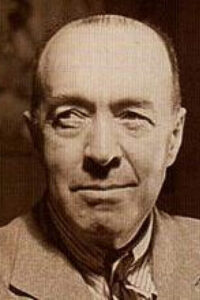

Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American writer, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best known for creating the characters Tarzan and John Carter, he also wrote the Pellucidar series, the Amtor series, and the Caspak trilogy. Tarzan was immediately popular, and Burroughs capitalized on it in every possible way, including a syndicated Tarzan comic strip, films, and merchandise. Tarzan remains one of the most successful fictional characters to this day and is a cultural icon. Burroughs’s California ranch is now the center of the Tarzana neighborhood in Los Angeles, named after the character. Burroughs was an explicit supporter of eugenics and scientific racism in both his fiction and nonfiction; Tarzan was meant to reflect these concepts.

Biography

Burroughs was born on September 1, 1875, in Chicago (he later lived for many years in the suburb of Oak Park), the fourth son of Major George Tyler Burroughs, a businessman, and Civil War veteran, and his wife, Mary Evaline (Zieger) Burroughs. His middle name is from his paternal grandmother, Mary Coleman Rice Burroughs. Burroughs was of almost entirely English ancestry, with a family line that had been in North America since the Colonial era. Through his Rice grandmother, Burroughs was descended from settler Edmund Rice, one of the English Puritans who moved to Massachusetts Bay Colony in the early 17th century. He once remarked: “I can trace my ancestry back to Deacon Edmund Rice.”

The Burroughs side of the family was also of English origin, having emigrated to Massachusetts around the same time. Many of his ancestors fought in the American Revolution. Some of his ancestors settled in Virginia during the colonial period, and Burroughs often emphasized his connection with that side of his family, seeing it as romantic and warlike. Burroughs was educated at several local schools. He then attended Phillips Academy, in Andover, Massachusetts, and then the Michigan Military Academy. Graduating in 1895, but failing the entrance exam for the United States Military Academy at West Point, he instead became an enlisted soldier with the 7th U.S. Cavalry in Fort Grant, Arizona Territory. After being diagnosed with a heart problem and thus ineligible to serve, he was discharged in 1897.

After his discharge, Burroughs worked at several different jobs. During the Chicago influenza epidemic of 1891, he spent half a year at his brother’s ranch on the Raft River in Idaho, as a cowboy, drifted somewhat afterward, then worked at his father’s Chicago battery factory in 1899, marrying his childhood sweetheart, Emma Hulbert (1876–1944), in January 1900. In 1903, Burroughs joined his brothers, Yale graduates George and Harry, who were, by then, prominent Pocatello area ranchers in southern Idaho, and partners in the Sweetser-Burroughs Mining Company, where he took on managing their ill-fated Snake River gold dredge, a classic bucket-line dredge. The Burroughs brothers were also the sixth cousins, once removed, of famed miner Kate Rice who, in 1914, became the first female prospector in the Canadian North. Journalist and publisher C. Allen Thorndike Rice was also his third cousin. When the new mine proved unsuccessful, the brothers secured for Burroughs a position with the Oregon Short Line Railroad in Salt Lake City. Burroughs resigned from the railroad in October 1904.

Later life

By 1911, around age 36, after seven years of low wages as a pencil-sharpener wholesaler, Burroughs began to write fiction. By this time, Emma and he had two children, Joan (1908–1972), and Hulbert (1909–1991). During this period, he had copious spare time and began reading pulp fiction magazines. In 1929, he recalled thinking that:

“[…] if people were paid for writing rot such as I read in some of those magazines, that I could write stories just as rotten. Although I had never written a story, I knew absolutely that I could write stories just as entertaining and probably a whole lot more so than any I chanced to read in those magazines.”

In 1913, Burroughs and Emma had their third and last child, John Coleman Burroughs (1913–1979), later known for his illustrations of his father’s books. In the 1920s, Burroughs became a pilot, purchased a Security Airster S-1, and encouraged his family to learn to fly. Daughter Joan married Tarzan film actor James Pierce. She starred with her husband as the voice of Jane, during 1932–1934 for the Tarzan radio series. Burroughs divorced Emma in 1934, and, in 1935, married the former actress Florence Gilbert Dearholt, who was the former wife of his friend (who was then himself remarrying), Ashton Dearholt, with whom he had co-founded Burroughs-Tarzan Enterprises while filming The New Adventures of Tarzan. Burroughs adopted the Dearholts’ two children. He and Florence divorced in 1942.

Burroughs was in his late 60s and was in Honolulu at the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Despite his age, he applied for and received permission to become a war correspondent, becoming one of the oldest U.S. war correspondents during World War II. This period of his life is mentioned in William Brinkley’s bestselling novel Don’t Go Near the Water.