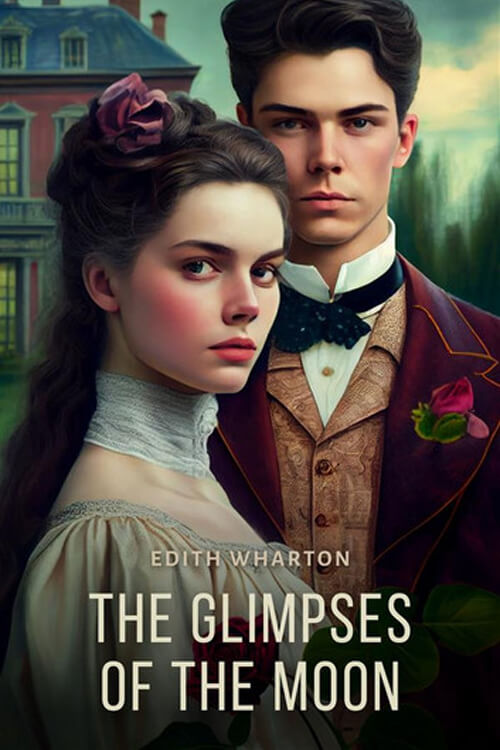

The Glimpses of the Moon

IT rose for them—their honeymoon—over the waters of a lake so famed as the scene of romantic raptures that they were rather proud of not having been afraid to choose it as the setting of their own.

“It required a total lack of humor, or as great a gift for it as ours, to risk the experiment,” Susy Lansing opined, as they hung over the inevitable marble balustrade and watched their tutelary orb roll its magic carpet across the waters to their feet.

“Yes—or the loan of Strafford’s villa,” her husband amended, glancing upward through the branches at a long low patch of paleness to which the moonlight was beginning to give the form of a white house-front.

“Oh, come when we’d five to choose from. At least if you count the Chicago flat.”

“So we had—you wonder!” He laid his hand on hers, and his touch renewed the sense of marveling exultation that the deliberate survey of their adventure always roused in her ….

It was characteristic that she merely added, in her steady laughing tone: “Or, not counting the flat—for I hate to brag-just consider the others: Violet Melrose’s place at Versailles, your aunt’s villa at Monte Carlo—and a moor!”

She was conscious of throwing in the moor tentatively, and yet with a somewhat exaggerated emphasis as if to make sure that he shouldn’t accuse her of slurring it over. But he seemed to have no desire to do so. “Poor old Fred!” he merely remarked; and she breathed out carelessly: “Oh, well—”

His hand still lay on hers, and for a long interval, while they stood silent in the enveloping loveliness of the night, she was aware only of the warm current running from palm to palm, as the moonlight below them drew its line of magic from shore to shore.

Nick Lansing spoke at last. “Versailles in May would have been impossible: all our Paris crowd would have run us down within twenty-four hours. And Monte Carlo is ruled out because it’s exactly the kind of place everybody expected us to go. So— with all respect to you—it wasn’t much of a mental strain to decide on Como.”

His wife instantly challenged this belittling of her capacity.

“It took a good deal of argument to convince you that we could face the ridicule of Como!”

“Well, I should have preferred something in a lower key; at least I thought I should till we got here. Now I see that this place is idiotic unless one is perfectly happy; and that then it’s-as good as any other.”

She sighed out a blissful assent. “And I must say that Streffy has done things to a turn. Even the cigars—who do you suppose gave him those cigars?” She added thoughtfully: “You’ll miss them when we have to go.”

Read or download Book

Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton (born Edith Newbold Jones; January 24, 1862 – August 11, 1937) was an American writer and designer. Wharton drew upon her insider’s knowledge of the upper-class New York “aristocracy” to portray realistically the lives and morals of the Gilded Age. In 1921, she became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, for her novel The Age of Innocence. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1996. Among her other well-known works are The House of Mirth, the novella Ethan Frome, and several notable ghost stories.

Biography

Edith Wharton was born Edith Newbold Jones on January 24, 1862, to George Frederic Jones and Lucretia Stevens Rhinelander at their brownstone at 14 West Twenty-third Street in New York City. To her friends and family, she was known as “Pussy Jones”. She had two elder brothers, Frederic Rhinelander and Henry Edward. Frederic married Mary Cadwalader Rawle; their daughter was landscape architect Beatrix Farrand. Edith was baptized on April 20, 1862, Easter Sunday, at Grace Church.

Wharton’s paternal family, the Joneses, were very wealthy and socially prominent having made their money in real estate. The saying “keeping up with the Joneses” is said to refer to her father’s family. She was related to the Rensselaers, the most prestigious of the old patroon families, who had received land grants from the former Dutch government of New York and New Jersey. Her father’s first cousin was Caroline Schermerhorn Astor. Fort Stevens in New York was named for Wharton’s maternal great-grandfather, Ebenezer Stevens, a Revolutionary War hero and general.

Wharton was born during the Civil War; however, in describing her family life Wharton does not mention the war except that their travels to Europe after the war were due to the depreciation of American currency. From 1866 to 1872, the Jones family visited France, Italy, Germany, and Spain. During her travels, the young Edith became fluent in French, German, and Italian. At the age of nine, she suffered from typhoid fever, which nearly killed her, while the family was at a spa in the Black Forest. After the family returned to the United States in 1872, they spent their winters in New York City and their summers in Newport, Rhode Island. While in Europe, she was educated by tutors and governesses. She rejected the standards of fashion and etiquette that were expected of young girls at the time, which were intended to allow women to marry well and to be put on display at balls and parties. She considered these fashions superficial and oppressive. Edith wanted more education than she received, so she read from her father’s library and the libraries of her father’s friends. Her mother forbade her to read novels until she was married, and Edith obeyed this command.