The Midnight Queen

The plague raged in the city of London. The destroying angel had gone forth and kindled with its fiery breath the awful pestilence until all London became one mighty lazar-house. Thousands were swept away daily; grass grew in the streets, and the living were scarce able to bury the dead. Business of all kinds was at an end, except that of the coffin-makers and drivers of the pest cart. Whole streets were shut up, and almost every other house in the city bore the fatal red cross and the ominous inscription, “Lord have mercy on us”. Few people, save the watchmen, armed with halberts, keeping guard over the stricken houses, appeared in the streets, and those who ventured there shrank from each other and passed rapidly on with averted faces.

Many even fell dead on the sidewalk and lay with their ghastly, discoloured faces, upturned to the mocking sunlight, until the dead cart came rattling along, and the drivers hoisted the body with their pitchforks on the top of their dreadful load. Few other vehicles besides those same dead carts appeared in the city now, and they plied their trade busily, day and night. The cry of the drivers echoed dismally through the deserted streets: “Bring out your dead! Bring out your dead!” All who could do so had long ago fled from the devoted city. London lay under the burning heat of the June sunshine, stricken for its sins by the hand of God.

The pesthouses were full, and so were the plague pits, where the dead were hurled in cartfuls; no one knew who rose in health in the morning but that they might be lying stark and dead in a few hours. The very churches were forsaken; their pastors fled or lying in the plague pits, and it was even resolved to convert the great cathedral of St. Paul into a vast plague hospital. Cries and lamentations echoed from one end of the city to another, and Death and Charles reigned over London together.

Yet in the midst of all this, many scenes of wild orgies and debauchery still went on within its gates—as, in our day, when cholera ravaged Paris, the inhabitants of that facetious city made it a carnival, so now, in London, they were many who, feeling they had but a few days to live at the most, resolved to defy death and indulge in the revelry while they yet existed. “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow you die!” was their motto, and if amid the frantic dance or debauched revel, one of them dropped dead, the others only shrieked with laughter, hurled the livid body out to the street, and the demoniac mirth grew twice as fast and furious as before. Robbers and cut-purses paraded the streets at noonday, entered boldly closed and deserted houses, and bore off with impunity, whatever they pleased.

Highwaymen infested Hounslow Heath and all the roads leading from the city, levying a toll on all who passed and plundering fearlessly the flying citizens. In the year of grace 1665, Far-famed London town would have given one a good idea if Pandemonium broke loose.

Read or download Book

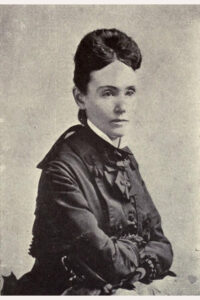

May Agnes Fleming

May Agnes Fleming (pseudonyms, Cousin May Carleton, M. A. Earlie; November 15, 1840 – March 24, 1880) was a Canadian novelist.

Biography.

She was “among the first Canadians to pursue a highly successful career as a popular fiction writer.” May Agnes Early was born in Carleton, West Saint John, in the Colony of New Brunswick, the daughter of Bernard and Mary Early. May Agnes began publishing while studying at school. She married an engineer, John W. Fleming, in 1865. She moved to New York two years after her first novel, Erminie, The gipsy’s Vow: A Tale of Love and Vengeance, was published there (1863). Under the pseudonym “Cousin May Carleton”, she published several serial tales in the New York Mercury and the New York Weekly.

Twenty-one were printed in book form, seven posthumously. She also wrote under the pseudonym “M.A. Earlie”. The exact count is unclear since her works were often retitled, but it is estimated at around 40. However, some were not written by her but were attributed to her by publishers cashing in on her popularity. At her peak, she earned over $10,000 yearly due to publishers granting her exclusive rights to her work. She died in Brooklyn, of Bright’s disease.