The Ordeal, A Mountain Romance of Tennessee

Nowhere could the idea of peace be expressed more serenely and majestically. The lofty purple mountains limited the horizon, and their multitude and imposing symmetry bespoke the vast intentions of kind creation. The valley, glooming low, harboured all the shadows. The air was still, the sky as transparent as crystal, and where a crag projected boldly from the forests, the growths of balsam fir extending almost to the brink, it seemed as if the myriad fibers of the summit line of foliage might be counted, so finely drawn, so individual, was each against the azure. Below the boughs, the road swept along the crest of the crag and thence curved inward, and one surveying the scene from the windows of a bungalow at no great distance could look straight beyond the point of the precipice and into the heart of the sunset, still aflare about the west.

But the realization of solitude was poignant and might well foster fear. It was too wild a country, many people said, for quasi-strangers, and the Briscoes were not justified in lingering so long at their summer cottage here in the Great Smoky Mountains after the hotel of the neighboring springs was closed for the season, and its guests and employees all vanished town-ward. Hitherto, however, the Briscoes had flouted the suggestion, protesting that this and not the spring was the “sweet o’ the year.” The autumn always found the fires flaring on the cozy hearths of their pretty bungalow, and they were wont to gaze entranced on the chromatic pageantry of the forests as the season waned. Presently the Indian summer would steal upon them unaware, with its wild sweet airs, the burnished glamours of its soft red sun, and its dreamy, poetic, amethystine haze. Now, too, came the crowning opportunity of sylvan sport. There were deer to stalk and to course with horses, hounds, and horns; wild turkeys and mountain grouse to try the aim and tax the pedestrianism of the hunter; bears had not yet gone into winter quarters, and were mast-fed and fat; even a shot at a wolf, slyly marauding, was no infrequent incident, and Edward Briscoe thought the place in autumn an Elysium for a sportsman.

He had to-day the prospect of a comrade in these delights from his own city home and of his rank in life, despite the desertion of the big frame hotel on the bluff, but it was not the enticement of rod and gun that had brought Julian Bayne suddenly and unexpectedly to the mountains. His host and cousin, Edward Briscoe, was his co-executor in a kinsman’s will, and in the settlement of the estate, the policy of granting a certain power of attorney necessitated a conference more confidential than could be safely compassed by correspondence. They discussed this as they sat in the spacious reception hall, and had Bayne been less preoccupied he must have noticed at once the embarrassment, nay, the look of absolute dismay, with which Briscoe had risen to receive him, when, unannounced, he appeared in the doorway as abruptly as if he had fallen from the clouds. As it was, the brief colloquy on the business interests that had brought him hither was almost concluded before the problem of his host’s manner began to intrude on Bayne’s consciousness. Briscoe’s broad, florid, genial countenance expressed an unaccountable disquietude; a flush had mounted to his forehead, which was elongated by his premature baldness; he was pulling nervously at his long dark mustache, which matched in tint the silky fringe of hair encircling his polished crown; his eyes, round and brown, and glossy as a chestnut, wandered inattentively. He did not contend on small points of feasibility, according to his wont—for he was of an argumentative habit of mind—in fact, his acquiescence in every detail proposed was so complete and so unexpected that Bayne, with half his urgency unsaid, came to the end of his proposition with as precipitate an effect as if he had stumbled upon it in the dark.

Read or download Book

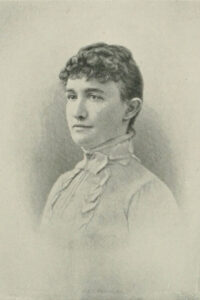

Mary Noailles Murfree

Mary Noailles Murfree (January 24, 1850 – July 31, 1922) was an American author of novels and short stories who wrote under the pen name Charles Egbert Craddock. She is considered by many to be Appalachia’s first significant female writer and her work is a necessity for the study of Appalachian literature, although several characters in her work reinforce negative stereotypes about the region. She has been favorably compared to Bret Harte and Sarah Orne Jewett, creating post-Civil War American local-color literature.

The town of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, is named after Murfree’s great-grandfather Colonel Hardy Murfree, who fought in the Revolutionary War.

Biography

Murfree was born on her family’s cotton plantation, Grantland, near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, a location later celebrated in her novel, Where the Battle was Fought, and in the town named after her great-grandfather, Colonel Hardy Murfree. Her father was a successful lawyer in Nashville, and her youth was spent in both Murfreesboro and Nashville. From 1867 to 1869 she attended the Chegary Institute, a finishing school in Philadelphia. Murfree would spend her summers in Beersheba Springs. For several years after the Civil War, the Murfree family lived in St. Louis, returning in 1890 to Murfreesboro, where she lived until her death.

Being lame from childhood, Murfree turned to reading the novels of Walter Scott and George Eliot. For fifteen successive summers, the family stayed in Beersheba Springs in the Cumberland Mountains of Tennessee, allowing her to study the mountains and mountain people more closely.

By the 1870s she had begun writing stories for Appleton’s Journal under the pen name of “Charles Egbert Craddock” and by 1878 she was contributing to the Atlantic Monthly. It was not until seven years later, in May 1885, that Murfree divulged that she was Charles Egbert Craddock to Thomas Bailey Aldrich, an editor at the Atlantic Monthly. Murfree visited the Montvale Springs resort near Knoxville, in 1886. Although she became known for the realism of her accounts she was from a wealthy family and would have had little contact with the local people while staying at the resorts.