The Red Rat’s Daughter

When a man is worth a hundred and twenty thousand pounds a year—which, worked out, means ten thousand pounds a month, three hundred and twenty-eight pounds, fifteen shillings and fourpence a day, and four-and-sixpence three-farthings, and a fraction over, per minute—he may surely be excused if he becomes a little skeptical as to other people’s motives, and is apt to be distrustful of the world in general. Old Brown, his father, without the “e,” as you have doubtless observed, started life as a bare-legged street arab in one of the big manufacturing centers—Manchester or Birmingham, I am not quite certain which. His head, however, must have been screwed on the right way, for he made few mistakes, and everything he touched turned to gold. At thirty his bank balance stood at fifteen thousand pounds; at forty it had turned the corner of a hundred thousand; and when he departed this transitory life, a young man in everything but years, he left his widow, young John’s mother—his second wife, I may remark in passing, and the third daughter of the late Lord Rushbrooke—upwards of three and a half million pounds sterling in trust for the boy.

As somebody wittily remarked at the time, young John, at his father’s death and during his minority, was a monetary Mohammed—he hovered between two worlds: the Rushbrookes, on one side, who had not two sixpences to rub against each other, and the Brownes, on the other, who reckoned their wealth in millions and talked of thousands as we humbler mortals do of half-crowns. Taken altogether, however, old Brown was not a bad sort of fellow. Unlike so many parvenus, he had the good sense, the “e” always excepted, not to set himself up to be what he certainly was not. He was a working man, he would tell you with a twinkle in his eye, and he had made his way in the world. He had never in his life owed a halfpenny, nor, to the best of his knowledge, had he ever defrauded anybody; and, if he had made his fortune out of soap, well—and here his eyes would glisten—soap was at least a useful article, and would wash his millions cleaner than a good many other commodities he might mention. In his tastes and habits, he was simplicity itself. Indeed, it was no unusual sight to see the old fellow, preparatory to setting off for the City, coming down the steps of his magnificent townhouse, dressed in a suit of rough tweed, with the famous bird’s-eye neck-cloth loosely twisted around his throat, and the soft felt hat upon his head—two articles of attire which no remonstrance on the part of his wife and no amount of ridicule from the comic journals could ever induce him to discard. His stables were full of carriages, and there was a cab rank within a hundred yards of his front door, yet no one had ever seen him set foot in either. The soles of his boots were thick, and he had been accustomed to walking all his life, he would say, and he had no intention of being carried till he was past caring what became of him.

Read or download Book

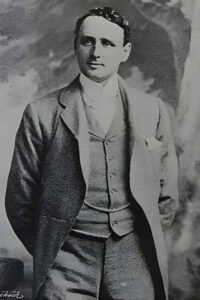

Guy Newell Boothby

Guy Newell Boothby (13 October 1867 – 26 February 1905) was a prolific Australian novelist and writer, noted for sensational fiction in variety magazines around the end of the nineteenth century. He lived mainly in England. He is best known for such works as the Dr Nikola series, about an occultist criminal mastermind who is a Victorian forerunner to Fu Manchu, and Pharos, the Egyptian, a tale of Gothic Egypt, mummies’ curses, and supernatural revenge. Rudyard Kipling was his friend and mentor, and his books were remembered with affection by George Orwell.

Biography

Boothby was born in Adelaide to a prominent family in the recently established British colony of South Australia. His father was Thomas Wilde Boothby, who for a time was a member of the South Australian Legislative Assembly, three of his uncles were senior colonial administrators, and his grandfather was Benjamin Boothby (1803–1868), controversial judge of the Supreme Court of South Australia from 1853 to 1867. When Boothby was aged approximately seven his English-born mother, whom he held in great regard, separated from his father and returned with her children to England. There he received a traditional English grammar school education at Salisbury, Lord Weymouth’s Grammar (now Warminster School), and Christ’s Hospital, London.

Following this, Boothby returned alone to South Australia at 16, where, in his turn, he entered the colonial administration as private secretary to the mayor of Adelaide, Lewis Cohen, but was “not contented” with the work. Despite Boothby’s family tradition of colonial service, his natural inclinations ran more to the creative than to the administrative and he was not satisfied with his limited role as a provincial colonial servant. In 1890, aged 23, Boothby wrote the libretto for Sylvia, a comic opera, published and produced at Adelaide in December 1890, and in 1891 his second show, The Jonquil: an Opera, appeared. He also wrote and performed in an operetta, Dimple’s Lovers, for Adelaide’s Garrick Club theatre group. The music in each case was written by Cecil James Sharp. His early literary ventures were directed at the theatre, but his ambition was not appeased by the lukewarm response his melodramas received in Adelaide. When severe economic collapse hit most of the Australian colonies in the early 1890s, he followed the well-beaten path to London in December 1891.

Boothby, however, was thwarted in his first bid for recognition as lack of funds forced him to disembark en route in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and begin making his way homewards through South East Asia. According to family legend, the dire poverty he faced on this journey led him to accept any kind of work he could get: ‘This meant working before the mast, stoking in ocean tramps, attending in a Chinese opium den in Singapore, digging in the Burmah Ruby fields, acting, prize fighting, cow punching…’ This was followed by a brief sojourn on Thursday Island, a Melanesian island in the Torres Strait group recently annexed by the Queensland colony, where he worked as a diver in the lucrative pearl trade; and finally by an arduous journey overland across the Australian continent home to Adelaide. While Depasquale, author of the only Boothby biography, warns that this account of his travels may be somewhat glamorous, Boothby certainly traveled extensively in South East Asia, Melanesia, and Australia during this period, collecting a stock of colonial anecdotes and experiences that were to influence much of his later writing.

Approximately two years later, Boothby finally reached London and succeeded in having an account of his peregrinations, On the Wallaby, or Through the East and Across Australia, published in 1894. The travelogue met with reasonable success, which was matched later that year by Boothby’s first novel, In Strange Company. A novel of adventure set variously in England, Australia, the South Seas, and South America, In Strange Company established a pattern that was to characterize the succeeding Boothby oeuvre – the use of exotic, international, and particularly Australasian locales that frequently function as an end in themselves superfluous to the requirements of the plot. By October 1895, Boothby had completed three further novels, including A Bid for Fortune, the first Dr Nikola novel which catapulted Boothby to wide acclaim. Of the two other novels Boothby wrote in 1895 A Lost Endeavour was set on Thursday Island and The Marriage of Esther ranged across several Torres Strait Islands. Boothby continued to produce fiction at a ferocious rate, producing up to six novels a year across the range of genres prevalent at the fin de siècle and is credited with producing over 53 novels in total, not to mention dozens of short stories and plays.