The Sahara

As one draws nearer, one is surprised to see that this town is not built on the shore and does not even have a port or direct means of communication with the outside world. The flat, unbroken coastline is as bleak as the Sahara’s, and a ridge of breakers forever prevents ships from approaching.

Another feature, not visible from a distance, now presents itself in the vast human and heaps on the shore, thousands and thousands of thatched huts, lilliputian dwellings with pointed roofs, and teeming with a grotesque population of negroes. The two large Yolof towns, Guet n’dar and N’dar-toute, lie between St Louis and the sea.

If your ship lies to awhile off this country, long pirogues with pointed bows like fish-heads and bodies shaped like sharks are soon seen approaching. They are manned by negroes, who row standing. These pirogue men are tall and lean, of Herculean proportions, admirable build, and muscular development, and their faces are those of gorillas. They have capsized ten times, at least while crossing the breakers. With negro perseverance, with the agility and strength of acrobats, ten times in succession have they righted their pirogue and made a fresh start. Sweat and seawater trickle from their bare skins, which gleam like polished ebony.

Here they are, despite all, smiling triumphantly and displaying their magnificent white teeth. Their costume consists of an amulet, a bead necklet, and their cargo of a carefully sealed leaden box containing the mail.

In this box are orders from the governor for the newly arrived ship, and papers addressed to colony members are also deposited.

A man in a hurry can safely entrust himself to these boatmen, secure in the knowledge that he will be fished out of the sea as often as necessary with the utmost care and eventually deposited on the beach.

But it is more comfortable to continue one’s voyage as far south as the mouth of the Senegal, where flat-bottomed boats take off the passengers and convey them smoothly by the river to St Louis.

This isolation from the sea is one of the chief causes of the stagnation and dreariness of this country. St Louis cannot serve as a port of call to mail steamers or merchantmen on their way to the southern hemisphere. One goes to St Louis if necessary, which gives one the feeling of being a prisoner cut off from the rest of the world.

Read or download Book

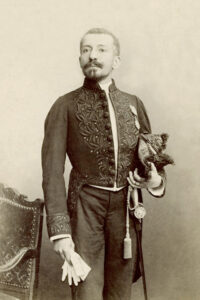

Pierre Loti

Pierre Loti ( pseudonym of Louis Marie-Julien Viaud 14 January 1850 – 10 June 1923) was a French naval officer and novelist, known for his exotic novels and short stories.

Biography

Born to a Protestant family, Loti’s education began in his birthplace, Rochefort, Charente-Maritime. At age 17 he entered the naval school in Brest and studied at Le Borda. He gradually rose in his profession, attaining the rank of captain in 1906. In January 1910 he went on the reserve list. He was in the habit of claiming that he never read books, saying to the Académie française on the day of his introduction (7 April 1892), “Loti ne sait pas lire” (“Loti doesn’t know how to read”), but testimony from friends proves otherwise, as does his library, much of which is preserved in his house in Rochefort. In 1876 fellow naval officers persuaded him to turn into a novel passage in his diary dealing with some curious experiences in Istanbul. The result was the anonymously published Aziyadé (1879), part romance, part autobiography, like the work of his admirer, Marcel Proust, after him.

Loti proceeded to the South Seas as part of his naval training, living in Papeete, Tahiti for two months in 1872, where he “went native”. Several years later he published the Polynesian idyll originally titled Rarahu (1880), which was reprinted as Le Mariage de Loti, the first book to introduce him to the wider public. His narrator explains that the name Loti was bestowed on him by the natives, after he mispronounced “roti” (a red flower). The book inspired the 1883 opera Lakmé by Léo Delibes. Loti Bain, a shallow pool at the base of the Fautaua Falls, is named for Loti.

This was followed by Le Roman d’un spahi (1881), a record of the melancholy adventures of a soldier in Senegal. In 1882, Loti issued a collection of four shorter pieces, three stories and a travel piece, under the general title of Fleurs d’ennui (Flowers of Boredom).

In 1883 Loti achieved a wider public spotlight. First, he published the critically acclaimed Mon Frère Yves (My Brother Yves), a novel describing the life of a French naval officer (Pierre Loti), and a Breton sailor (Yves Kermadec, inspired by Loti companion Pierre le Cor), described by Edmund Gosse as “one of his most characteristic productions”. Second, while serving in Tonkin (northern Vietnam) as a naval officer aboard the ironclad Atalante, Loti published three articles in the newspaper Le Figaro in September and October 1883 about atrocities that occurred during the Battle of Thuận An (20 August 1883), and attack by the French on the Vietnamese coastal defenses of Hue. He was threatened with suspension from the service for this indiscretion, thus gaining wider public notoriety. In 1884 his friend Émile Pouvillon dedicated his novel L’Innocent to Loti.

In 1886 Loti published a novel of life among the Breton fisherfolk, called Pêcheur d’Islande (An Iceland Fisherman), which Edmund Gosse characterized as “the most popular and finest of all his writings. It shows Loti adapting some of the Impressionist techniques of contemporary painters, especially Monet, to prose, and is a classic of French literature. In 1887 he brought out a volume “of extraordinary merit, which has not received the attention it deserves”, Propos d’exil, a series of short studies of exotic places, in his characteristic semi-autobiographic style. Madame Chrysanthème, a novel of Japanese manners that is a precursor to Madama Butterfly and Miss Saigon (a combination of narrative and travelogue) was published the same year.