The Vagrant Duke

The British refugee ship Phrygia was about to sail for Constantinople, and her unfortunate passengers were to be transferred to other vessels sailing for Liverpool and New York. After some difficulties, the refugee made his way aboard her and announced his identity to the captain. If he had expected to be received with the honor due to one of his rank and station he was quickly undeceived, for Captain Blashford, a man of rough manners, concealing a gentle heart, looked him over critically, examined his credentials (letters he had happened to have about him), and then smiled grimly.

“We’ve got room for one more—and that’s about all.”

“I have no money——” began the refugee.

“Oh, that’s all right,” shrugged the Captain, “you’re not the only one. We have a cargo of twenty princes, thirty-two princesses, eighteen generals, and enough counts and countesses to set up a new nation somewhere. Your ‘Ighness is the only Duke that has reached us up to the present speakin’ and if there are any others, they’ll ‘ave to be brisk for we’re sailin’ in twenty minutes.”

The matter-of-fact tones with which the unemotional Britisher made this announcement restored the lost sense of humor of the Russian refugee, and he broke into a grim laugh.

“An embarrassment of riches,” remarked the Grand Duke.

“Riches,” grunted the Captain, “in a manner of speakin’, yes. Money is not so plentiful. But Jools! Good God! There must be half a ton of diamonds, rubies, and emeralds aboard. All they’ve got left most of ’em, but complaints and nervousness. Give me a cargo of wheat and I’m your man,” growled the Captain. “It stays put and doesn’t complain,” and then turning to Peter—”Ye’re not expectin’ any royal suite aboard the Phrygia, are ye?”

“No. A hammock forward will be good enough for me.”

“That’s the way I like to ‘hear a man talk. Good God! As man to man, I ask you,—with Counts throwin’ cigarette butts around an’ princesses cryin’ all over my clean white decks an’ all, what’s a self-respectin’ skipper to do? But I ‘ave my orders to fetch the odd lot to Constantinople an’ fetch ’em I will. Oh! They’re odd—all right. Go below, sir, an’ ‘ave a look at ’em.”

Read or download Book

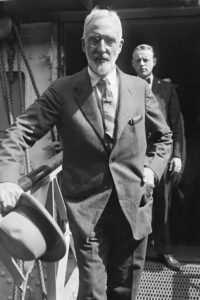

George Gibbs

George Fort Gibbs (March 8, 1870 – October 10, 1942) was an American author, illustrator, artist, and screenwriter. As an author, he wrote more than 50 popular books, primarily adventure stories revolving around espionage in “exotic” locations. Several of his books were made into films. His illustrations appeared prominently in such magazines as The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies Home Journal, Redbook, and The Delineator. He also illustrated some of his novels and the novels of others. As a painter, he produced many portraits and painted murals for Pennsylvania Station and Girard College in Philadelphia. His screenwriting credits include a film about the life of Voltaire.

Biography

George Gibbs was born in 1870 in New Orleans. His father, Benjamin F. Gibbs, was a naval surgeon with the ironclad fleet stationed there. Dr. Gibbs had seen many adventures in his naval career. He had taken part in the Paraguay Expedition aboard the USS Mystic. During the American Civil War, he had taken part in the battle of Mobile Bay aboard the steam sloop USS Ossipee and had been aboard one of the ships that chased the CSS Webb on its dash down the Mississippi.

In mid-war, on February 25, 1864, Dr. Gibbs married Elizabeth Beatrice Kellogg. The bride’s father, Major George Kellogg, was a homeopathic doctor brought to occupied New Orleans by General Nathaniel P. Banks, commander of the Army of the Gulf, and assigned to various duties as army surgeon, and as medical advisor to the family of General Banks. Nine months after their marriage, Mrs. Gibbs gave birth to a daughter, Julie Aline Gibbs. In 1870 a son, George Fort Gibbs, was born.

Dr. Gibbs continued to rise in the navy, ultimately attaining the rank of Medical Inspector and being designated Fleet Surgeon of the European Squadron on August 20, 1881. He took Elizabeth, Aline, and George with him, settling them in Geneva, where George was enrolled as a student at the Chateau de Lancy for two years. Chateau de Lancy also educated such men as William Carlos Williams, Sir Harold Acton, and Hamilton Fish. In September 1882, while aboard the USS Lancaster sailing for Trieste, Dr. Gibbs became seriously ill. According to one source, he was probably suffering from “malarial fever”. When the ship reached port, he was immediately moved to a hospital, where he died on September 9. His son George was twelve years old at the time.

Elizabeth Gibbs was extremely distraught over her husband’s death. The family returned to the United States in November 1883, debarking in New York and then taking a train bound for Washington, D.C., where Elizabeth’s father awaited them. George was then thirteen years old, and Aline eighteen. The children were concerned about their mother, who had expressed thoughts of suicide. As the train approached Union Station (at the site of what is now Penn Station) in Baltimore, Elizabeth left her children and entered the ladies’ restroom. She was gone for a long time, and the children began to worry. When the train arrived at the station they tried the door of the restroom, but it was locked. George climbed up to a transom and looked in, only to find the room empty, and its window open.

The children notified railroad officials, who sent an engine back down the tracks to look for Elizabeth. Aline went ahead to D.C., to meet with her grandfather, and George stayed behind with the searchers. Later that day Aline received a telegram from George, telling her that their mother had been found lying on the tracks a few miles from the station. Her skull was fractured, and she was taken to a hospital, where she died soon after. She had climbed six feet up to the window and leaped from the train, landing on her head.