Timothy Crump’s Ward

It was drawing towards the close of the last day of the year. A few hours more, and 1836 would be no more.

It was a cold day. There was no snow on the ground, but it was frozen into stiff ridges, making it uncomfortable to walk upon. The sun had been out all day, but there was little heat or comfort in its bright, but frosty beams.

The winter is a hard season for the poor. It multiplies their necessities, while, in general, it limits their means and opportunities of earning. The winter of 1836-37 was far from being an exception to this rule. It was worse than usual, on account of the general stagnation of business.

In a humble tenement, located on what was then the outskirts of New York, though today a granite warehouse stands on the spot, lived Timothy Crump, an industrious cooper. His family consisted of a wife and one child, a boy of twelve, whose baptismal name was John, though invariably addressed, by his companions, as Jack.

There was another member of the household who would be highly offended if she were not introduced, in due form, to the reader. This was Miss Rachel Crump, maiden sister of Uncle Tim, as he was usually designated.

Miss Rachel was not much like her brother, for while the latter was a good-hearted, cheerful easy man, who was inclined to view the world in its sunniest aspect, Rachel was cynical, and given to misanthropy. Poor Rachel, let us not be too hard upon thy infirmities. Could we lift the veil that hides the secrets of that virgin heart, it might be, perchance, that we should find a hidden cause, far back in the days when thy cheeks were rounder and thine eyes brighter, and thine aspect not quite so frosty. Ah, faithless Harry Fletcher! thou hadst some hand in that peevishness and repining which make Rachel Crump, and all about her, uncomfortable. Lured away by a prettier face, you left her to pass through life, unblessed by that love which every female heart craves, and for which no kindred love will compensate. It was your faithlessness that left her to walk, with repining spirit, the flinty path of the old maid.

Yes; it must be said—Rachel Crump was an old maid; not from choice, but hard necessity. And so, one by one, she closed up the avenues of her heart and clothed herself with complaining, as with a garment. Being unblessed with earthly means, she had accepted the hearty invitation of her brother, and become an inmate of his family, where she paid her board by little services about the house, and obtained sufficient needlework to replenish her wardrobe as often as there was occasion. Forty-five years had now rolled over her head, leaving clearer traces of their presence, doubtless, than if her spirit had been more cheerful; so that Rachel, whose strongly marked features never could have been handsome, was now undeniably homely.

Read or download Book

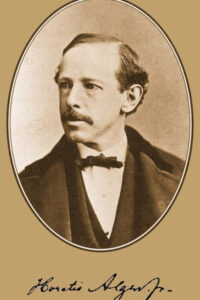

Jr. Alger Horatio

Horatio Alger Jr. (January 13, 1832 – July 18, 1899) was an American author who wrote young adult novels about impoverished boys and their rise from humble backgrounds to middle-class security and comfort through good works. His writings were characterized by the “rags-to-riches” narrative, which had a formative effect on the United States from 1868 through to his death in 1899.

Alger secured his literary niche in 1868 with the publication of his fourth book, Ragged Dick, the story of a poor bootblack’s rise to middle-class respectability. This novel was a huge success. His many books that followed were essentially variations on Ragged Dick and featured stock characters: the valiant, hardworking, honest youth; the noble mysterious stranger; the snobbish youth; and the evil, greedy squire. In the 1870s, Alger’s fiction was growing stale. His publisher suggested he tour the Western United States for fresh material to incorporate into his fiction. Alger took a trip to California, but the trip had little effect on his writing: he remained mired in the staid theme of “poor boy makes good”. The backdrops of these novels, however, became the Western United States, rather than the urban environments of the Northeastern United States.

Biography

Childhood: 1832–1847

Alger was born on January 13, 1832, in the New England coastal town of Chelsea, Massachusetts, the son of Horatio Alger Sr., a Unitarian minister, and Olive Augusta Fenno. He had many connections with the New England Puritan aristocracy of the early 19th century. He was the descendant of Pilgrim Fathers Robert Cushman, Thomas Cushman, and William Bassett. He was also the descendant of Sylvanus Lazell, a Minuteman and brigadier general in the War of 1812, and Edmund Lazell, a member of the Constitutional Convention in 1788. Alger’s siblings Olive Augusta and James were born in 1833 and 1836, respectively. An invalid sister, Annie, was born in 1840, and a brother, Francis, in 1842. Alger was a precocious boy afflicted with myopia and asthma, but Alger Sr. decided early that his eldest son would one day enter the ministry. To that end, Alger’s father tutored him in classical studies and allowed him to observe the responsibilities of ministering to parishioners. Alger began attending Chelsea Grammar School in 1842, but by December 1844 his father’s financial troubles had worsened considerably. In search of a better salary, he moved the family to Marlborough, Massachusetts, an agricultural town 25 miles west of Boston, where he was installed as pastor of the Second Congregational Society in January 1845 with a salary sufficient to meet his needs. Alger attended Gates Academy, a local preparatory school, and completed his studies at age 15. He published his earliest literary works in local newspapers.

Personal life

Scharnhorst writes that Alger “exercised a certain discretion in discussing his probable homosexuality” and was known to have mentioned his sexuality only once after the Brewster incident. In 1870, Henry James Sr. wrote that Alger “talks freely about his late insanity—which he appears to enjoy as a subject of conversation”. Although Alger was willing to speak to James, his sexuality was a closely guarded secret. According to Scharnhorst, Alger made veiled references to homosexuality in his boys’ books, and these references, Scharnhorst speculates, indicate Alger was “insecure with his sexual orientation”. Alger wrote, for example, that it was difficult to distinguish whether Tattered Tom was a boy or a girl, and in other instances, he introduces foppish, effeminate, lisping “stereotypical homosexuals” who are treated with scorn and pity by others. In Silas Snobden’s Office Boy, a kidnapped boy disguised as a girl is threatened with being sent to the “insane asylum” if he should reveal his actual sex. Scharnhorst believes Alger’s desire to atone for his “secret sin” may have “spurred him to identify his charitable acts of writing didactic books for boys with the acts of the charitable patrons in his books who wish to atone for a secret sin in their past by aiding the hero”. Scharnhorst points out that the patron in Try and Trust, for example, conceals a “sad secret” from which he is redeemed only after saving the hero’s life.

Alan Trachtenberg, in his introduction to the Signet Classic edition of Ragged Dick (1990), points out that Alger had tremendous sympathy for boys and discovered a calling for himself in the composition of boys’ books. “He learned to consult the boy in himself”, Trachtenberg writes, “to transmute and recast himself—his genteel culture, his liberal patrician sympathy for underdogs, his shaky economic status as an author, and not least, his dangerous erotic attraction to boys—into his juvenile fiction”. He observes that it is impossible to know whether Alger lived the life of a secret homosexual, “[b]ut there are hints that the male companionship he describes as a refuge from the streets—the cozy domestic arrangements between Dick and Fosdick, for example—may also be an erotic relationship”. Trachtenberg observes that nothing prurient occurs in Ragged Dick but believes the few instances in Alger’s work of two boys touching or a man and a boy touching “might arouse erotic wishes in readers prepared to entertain such fantasies”. Such images, Trachtenberg believes, may imply “a positive view of homoeroticism as an alternative way of life, of living by sympathy rather than aggression”. Trachtenberg concludes, “in Ragged Dick we see Alger plotting domestic romance, complete with a surrogate marriage of two homeless boys, as the setting for his formulaic metamorphosis of an outcast street boy into a self-respecting citizen”.