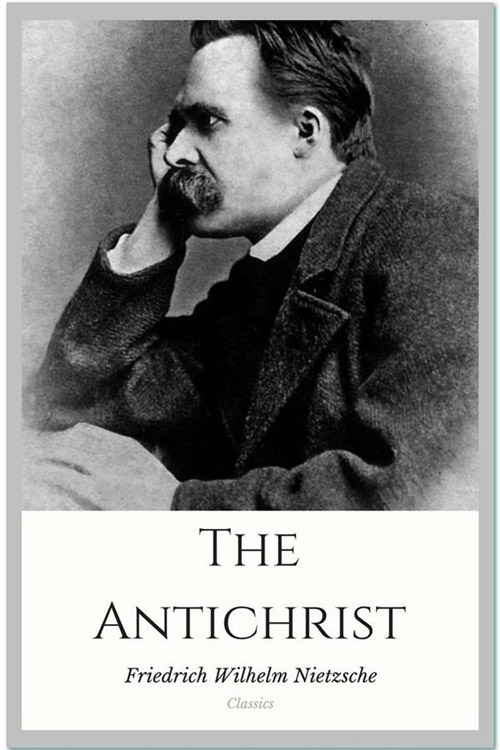

The Antichrist (Der Antichrist)

During his dark days of neglect and misunderstanding, when even family and friends kept aloof, Frau Förster-Nietzsche went with him farther than any other. Still, there were bounds beyond which she also hesitated to go, and crosses marked those bounds. One notes, in her biography of him—a useful but not consistently accurate work—an evident desire to purge him of the accusation of mocking sacred things. He had, she says, great admiration for “the elevating effect of Christianity … upon the weak and ailing,” “a real liking for sincere, pious Christians,” and “a tender love for the Founder of Christianity.”

All his wrath, she continues, was reserved for “St. Paul and his like,” who perverted the Beatitudes, which Christ intended for the lowly only, into a universal religion that made war upon aristocratic values. Here, one is addressed by an interpreter who cannot forget that she is the daughter of a Lutheran pastor and the granddaughter of two others; a touch of conscience gets into her reading of “The Antichrist.” She even hints that some more sinister heretic may have misinterpreted the text after the author’s collapse. There is not the slightest reason to believe that any such garbling ever took place, nor is there any evidence that their common heritage of holiness rested upon the brother as heavily as it rested upon the sister.

On the contrary, it must be manifest that Nietzsche, in this book, intended to attack Christianity headlong and with all arms, that for all his rapid writing, he put the utmost care into it and that he wanted it to be printed exactly as it stands. The ideas in it were anything but new to him when he set them down. He had been developing them since the days of his beginning. You will find some of them, clearly recognizable, in the first book he ever wrote, “The Birth of Tragedy.” You will find the most important conception of Christianity as ressentiment—set forth at length in the first part of “The Genealogy of Morals,” published under his supervision in 1887. And the rest are scattered through the vast mass of his notes, sometimes as mere questionings but often worked out very carefully.

Moreover, let it not be forgotten that Wagner’s yielding to Christian sentimentality in “Parsifal” transformed Nietzsche from the first among his literary advocates into the most bitter of his opponents. He could forgive every other sort of mountebankery, but not that. “In me,” he once said, “the Christianity of my forbears reaches its logical conclusion. In me, the stern intellectual conscience that Christianity fosters and makes paramount turns against Christianity. In me, Christianity … devours itself.”

Read or download Book

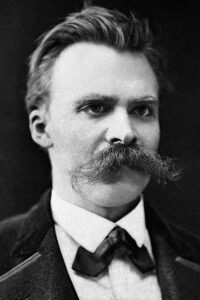

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher.

Biography.

He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest person to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869 at 24. However, he resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life; he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterwards a complete loss of his mental faculties, with paralysis and probably vascular dementia. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until she died in 1897 and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Nietzsche died in 1900 after experiencing pneumonia and multiple strokes.

Nietzsche’s work spans philosophical polemics, poetry, cultural criticism, and fiction while displaying a fondness for aphorism and irony. Prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical critique of truth in favour of perspectivism, a genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality and a related theory of master–slave morality; the aesthetic affirmation of life in response to both the “death of God” and the profound crisis of nihilism; the notion of Apollonian and Dionysian forces; and a characterization of the human subject as the expression of competing wills, collectively understood as the will to power. He also developed influential concepts such as the Übermensch and his doctrine of eternal return. In his later work, he became increasingly preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome cultural and moral mores in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health. His work touched on many topics, including art, philology, history, music, religion, tragedy, culture, and science. It drew inspiration from Greek tragedy and figures such as Zoroaster, Arthur Schopenhauer, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Richard Wagner, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

After his death, Nietzsche’s sister, Elisabeth, became the curator and editor of his manuscripts. She edited his unpublished writings to fit her German ultranationalist ideology, often contradicting or obfuscating Nietzsche’s stated opinions, which were explicitly opposed to antisemitism and nationalism. Through her published editions, Nietzsche’s work became associated with fascism and Nazism. 20th-century scholars such as Walter Kaufmann, R. J. Hollingdale, and Georges Bataille defended Nietzsche against this interpretation, and corrected editions of his writings were soon made available. Nietzsche’s thought enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1960s, and his ideas have since had a profound impact on 20th- and early 21st-century thinkers across philosophy—especially in schools of continental philosophy such as existentialism, postmodernism, and post-structuralism—as well as art, literature, poetry, politics, and popular culture.

Life

Youth (1844–1868)

Born on 15 October 1844, Nietzsche grew up in the town of Röcken (now part of Lützen), near Leipzig, in the Prussian Province of Saxony. He was named after King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, who turned 49 on the day of Nietzsche’s birth (Nietzsche later dropped his middle name, Wilhelm). Nietzsche’s parents, Carl Ludwig Nietzsche (1813–1849), a Lutheran pastor and former teacher, and Franziska Nietzsche (née Oehler) (1826–1897), married in 1843, the year before their son’s birth. They had two other children: a daughter, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, born in 1846, and a second son, Ludwig Joseph, born in 1848. Nietzsche’s father died from a brain disease in 1849, after a year of excruciating agony, when the boy was only four years old; Ludwig Joseph died six months later at age two. The family then moved to Naumburg, living with Nietzsche’s maternal grandmother and his father’s two unmarried sisters. After the death of Nietzsche’s grandmother in 1856, the family moved into their own house, now Nietzsche-Haus, a museum and study centre.